This article is offered as an outline and reference guide to share and convey my understandings and working knowledge of attachment processes and traumas experienced by the developing psyche, and the effects of these. Such processes have a tendency to emerge later in life in the form of various interpersonal difficulties, emotional suffering, personality disorders, addictive behaviors, dissociative fracturing, enmeshed personal relationships, avoidance and denial processes, and other obstacles to living an integrated and empowered life.

(The information in this article is summarized in outline form at the end of the article for those who would find summary of the concepts useful in that form).

My conceptualization of these matters derives from ten years of observation and inquiry through clinical work in the practice of psychotherapy, my internal observations through personal work with my own emotional and trauma processes, and supplementary inquiry through a synthesis of various approaches to the understanding the human condition in the fields of psychology, philosophy, spirituality, mythology, art, and healing.

I have found the following conceptual framework to represent an applicable and flexible approach to understanding the internal processes and external behaviors found within the self and observed in others. I also find that it offers an accessible and clarifying approach to self-development on the personal healing journey.

It should be understood that the terms I use in this outline may be terms that are used differently by other writers, researchers, and healers working in this field. In particular, the terms narcissism and codependency are referred to here as processes of the psyche that are universal, or near universal, in the human experience. As such, they are to be understood as processes that vary and fluctuate in intensity between differing psyches, and in response to the changeable circumstances such psyches may encounter throughout the lifespan.

Foundations:

Narcissistic Process – This refers to the projective function of the psyche, which could also be referred to as an imaginative, visioning, fantasy, or dreaming function. In it, the mind projects realities that do not exist (as of yet) onto the self, onto others, and onto the world. This function is vital and necessary to human life in many ways. We use it to summon internal motivation and hope for change, and to envision unrealized possibilities that can then be brought into being through creative endeavor.

The projective function can be understood in terms of constituting a narcissistic process (through the terminology I am using here) when it runs contrary to the reality-testing function of the ego—and when the psyche prefers the projective reality to the reality arrived at through the egoic function of comparing and testing one’s presuppositions against external evidence and experience.

This preference for projective fantasy rather than externally verified and moderated pictures of reality can occur through a variety of means. Generally speaking, it can be understood that in psyches dominated by a pronounced narcissistic process, ego development was impaired and arrested during childhood as a result of traumatic, neglectful, and enmeshed attachment experiences. The projective function is relied upon to compensate and cope with states of overwhelm, shame, confusion, and emotional dysregulation.

Through compartmentalization, memory-editing, memory-holing, denial, avoidance, and conflict processes, along with the continuous creation of new projections, the narcissistic psyche is able to defend itself against the intrusions of the external world that threaten to tear apart its internal consistency.

Codependent Process – This term refers to the introjective function of the psyche, in which the psyche receives external projections and incorporates them into its own conceptualization of self, others, and the world. Through introjection, the psyche alters its own beliefs, self-concept, values, and goals to align with the assigned beliefs, values, goals, and self-concept imposed from without.

As with the narcissistic process, the introjective function of the psyche is referred to here as a codependent process when externally derived introjects overwhelm the ego’s reality-testing process, and are adhered to by the psyche in spite of countervailing evidence (whether external or internal). The codependent process also forms as a result of impaired ego development in childhood as a result of abuse, neglect, or enmeshed attachment processes.

When operating under the influence of a codependent process, the psyche will internalize a negative self-concept with a self-critical thought process and belief system. The process is characterized by attempts to discern externally derived rules or expectations, and to comply with such rules and expectations in order to be considered “good,” and/or to compensate for internal feelings of shame and “badness.” In a codependent process, the introjected beliefs and fears about low self-worth resist the ego’s reality-testing function in their resilience, and in spite of contravening evidence of self-worth. An active codependent process will increase a person’s vulnerability to accepting abusive treatment and gaslighting from others due to pervasive self-doubt and difficulties determining that abusive treatment is unwarranted, or that it is even occurring.

Avoidance refers to any activity or mental state that is engaged for the purpose of shielding the psyche from emotional distress or overwhelm. Avoidance can be pursued on either a conscious or unconscious level. One of the most common forms of avoidance is an addictive process. Repetitive, methodical, and habitual activities can have a soothing effect on the emotional system, especially when punctuated by periodic “reward” experiences (like leveling up in a video game). Substance use can also achieve the effect of blunting or numbing the emotions on a biochemical level.

Avoidance activities distract attention from experiences of emotional distress, or from the conditions which give rise to emotional distress. They can soothe and regulate the emotions, or delay the experience of them through procrastination. Unconscious and involuntary forms of avoidance include dissociation, brain fog, memory lapses, blocked memories, and nervous collapse.

Avoidance can also occur in a complex and roundabout fashion, conspiring to maintain false narratives and false views of self or others. The psyche relies on these to avoid experiencing the traumatic grief at the foundations of the deep-seated attachment trauma which forms the core of codependent and narcissistic processes. Complex avoidance processes create recurring behavior patterns, such as addiction and self-sabotage. These generate obstacles and distractions to the removal of the core beliefs formed in response to attachment trauma, and even reinforce the self-defeating narratives that keep codependent and narcissistic processes in place. From a certain perspective, both narcissistic and codependent processes represent a complex avoidance network constructed and maintained by the psyche to protect against traumatic grief, overwhelm, and despair.

Formation of Narcissistic and Codependent Processes

Narcissistic and codependent processes represent opposite and complementary poles of compensatory attachment trauma responses in the psyche’s conception of self and relation to others.

Attachment trauma can also be referred to as attachment wounding, or enmeshment wounding. These terms (slightly different in reference, but for the most part synonymous), refer to wounds or injuries suffered by the developing psyche in childhood, most notably when the wounds are received from the child’s primary caregivers. Attachment wounding can also occur in experiences with siblings and other family members, authority figures outside of the home (such as teachers), or from peers through bullying or other forms of abuse.

To the extent that the attachment wounds are received from people other than the primary caregivers, an underlying attachment wound is also formed (or reinforced) with reference to those primary caregivers—due to the caregivers’ failure (experienced as neglect) to protect the child from this harm. It is also typically the case that if a child has a strong and healthy relationship with the primary caregivers (with minimal attachment wounding or enmeshment), the interpersonal traumas received from others will be less harmful to the child’s psyche.

Enmeshment refers to the overlap (or total lack) of boundaries between the child and (usually) a primary caregiver (or between adults later in life). This term has commonly been used to refer to relationships exhibiting an extreme degree of overlap and entanglement between two individuals, but as with codependence and narcissism, I find it much more useful to understand enmeshment as a process that exists on a spectrum. From outright abuse, to emotional neglect, to ordinary processes of confusion between self and others, the concept of enmeshment illuminates a broad understanding of interpersonal distress and attachment trauma.

With abuse, the abuser violates the child’s boundaries—the abuser’s needs are prioritized above the child’s boundaries or needs to a gross degree. This bulldozing of the child’s boundaries invariably creates confusion and overwhelm in the child’s psyche. The abuse forms an introject that carries the following types of messages to the child: “You want this treatment. I am you. This is the correct thing for you. If you think you don’t want this, you are wrong. You are either wrong for not wanting it, or wrong for thinking you don’t want it.” Or: “You are bad. You have done something wrong. This bad experience is the correct treatment for you because of your badness or the bad things you have done.” Abuse feels like love. Love feels like abuse. Everything that feels good also feels bad and vice versa. All propositions are reversed.

The abuse introject is internalized into the child’s psyche, creating identity confusion and fracturing. It splits the natural self-affirming state of the psyche against itself. This natural self-affirming state can be understood as the true self. This is the self that knows what it wants, knows what it doesn’t want, trusts what it wants and doesn’t want implicitly, and affirms “I have a right to be here. It is inherently good and right that I exist as I am.” One can intuit this basic state in the wild beings of the plant and animal world who make no apologies for their existence as they are. And we can intuit this basic identity state within ourselves: it is the life force that creates and animates our body, breathes our air, digests our food, and heals our wounds.

The introject that enters the psyche through enmeshment confuses the child’s sense of self and the inherent sense of goodness in the self. The child is neither physically, mentally, nor emotionally developed enough to be independent of caregivers, and the child is also not developed enough to fully understand what is happening. The abusive caregiver has become what is called a bad object, but the child’s psyche is too overwhelmed, attached, and dependent on the caregiver to regard them as bad. Thus, the bad object is projected inward, and integrated into the child’s psyche as an introject (protecting the positive image of the caregiver). This introject becomes confused with the child’s own sense of self, creating fracturing.

Types of Enmeshment Wounding

When fractured, the psyche is divided against itself between the self-affirming true self and the self-abasing abused self, or internalized bad object. The two selves cannot be reconciled, and the experience of dissonance between these two selves creates the emotion of shame. Abuse is only one form of enmeshment that creates fracturing. Neglect is also a profound and very powerful source of attachment trauma.

Enmeshment wounding can also occur through methods that are not often thought of as either abuse or neglect. For instance, a parent may project identities onto the child, even positively-regarded identities, such as “the golden child” archetype, placing the child on a pedestal. By doing so, the child is not accurately seen, and instead is seen as the parent’s projection (which has become the child’s introject), creating identity confusion, pressure, and a feeling of invisibility in the child. The child has been utilized as an object in service of the parent’s needs.

An enmeshment wound (which constitutes attachment trauma) can be summarized as any instance in which the child is utilized as an object in service of the primary caregiver’s needs. Thus, emotional neglect is to be understood as constituting an enmeshment wound just as surely as abuse. The parent’s need to either ignore the child or project false identities onto the child (whether to serve the parents’ goals of emotional satisfaction or avoidance, pleasure-seeking, addiction, career advancement, or anything else) creates a bad object introject in the child. This introject carries the message that the child’s true personality, emotional state, and needs don’t matter, don’t exist, or are wrong—and that these are to be superseded by and replaced with the parents’ emotional or material needs.

In many cases, neglect may even create deeper attachment wounds than straightforward abuse. In the case of abuse, the child has a sense of mattering enough to at least be an object of abuse. When neglected, the child receives the message, “I don’t even matter enough to be abused. I am nothing at all.” Moreover, emotional neglect is often invisible, even to the recipient. This both amplifies the damage incurred by the psyche (not only is the child unseen, even the harm suffered by the child is unseen), and compounds gaslighting wounds, heightening the discrepancy between the child’s unhappy internal state, and the false image of a stable and supportive external family environment.

In addition to neglect and emotional neglect, which carry the message “you don’t matter,” other important enmeshment wounds include inaccurate mirroring, when the parent imposes identity projections onto the child (or simply ignores the child) instead of seeing the child accurately and reflecting that recognition back to the child. Gaslighting is another key enmeshment wound. Broadly applied, it is another term for inaccurate mirroring and forms an inevitable component of all enmeshment wounding. Gaslighting can be summarized as the imposition of an identity or internal truth onto another that contradicts that person’s own identity or internal truth. Gaslighting tells another person how they are and what they are like with the force of authority, representing an aggressive attempt to define that person and that person’s reality from without.

Other enmeshment wounds include conditional love, in which the parent withdraws affection to punish the child for not conforming to the parent’s desires, or withholds affection as a baseline and bestows scarce glimmers of affection to reward the child for compliance. Physical and sexual abuse impose harm on the child’s body, or violate the child’s body and boundaries to satisfy the abuser’s whims, moods, sadism, or urges. Due to the overwhelming compounded boundary violations and enmeshment confusion experienced through sexual abuse, sexual abuse is typically the most profound type of enmeshment wound that can occur.

Verbal abuse constitutes an extreme form of gaslighting in which the child is disparaged and shamed with devaluing projections. Imposing chaos on the child’s experience (such as witnessing abuse) is another way of creating an enmeshment wound in the child. Inconsistency, unreliability, and exposure to risk of harm leads to confusion, chronic states of fear, and learned helplessness in the child. Parentification of a child occurs when a child is required to attend to and caretake the parent’s emotional or material needs in a direct way. Since this is a component of all enmeshment wounding, the creation of a parentified child can be understood as a component of all attachment trauma to some degree.

Anatomy of the Fractured Self

At the most basic level, enmeshment fracturing results in the child disowning part of the self, creating an exiled part, or shadow. From this initial fracture, subsequent fractures and formulations of the psyche’s parts can proceed with a complexity unique to each individual. The overall dynamic is the struggle to disidentify with the bad object introject that has been exiled into the shadow of the psyche and achieve a positive self-concept. Most of the fractured parts can be understood as fractures within the inner child. As an adult recovering from attachment trauma, these child parts have a tendency to hijack the psyche when activated by trauma cues, acute stress, or prolonged deprivation of interpersonal needs.

Among the commonly identified child parts are two basic permutations of the parentified child, each playing the role of a parent. One plays the role of the strict, punishing, unforgiving critical parent; the other plays the role of the permissive, neglectful, chaotic parent. Each of these parts does not realize they are a child part, and experiences distress and overwhelm attempting to parent the psyche and keep the exiled, bad object child part at bay. The strict parent punishes the psyche with harsh and disparaging self-critical reprimands, heaping blame and shame on the self for various failures or perceived failures. Other times, the permissive parent is activated and attempts to mollify the psyche with indulgent pleasure and avoidance: food, drugs, sex, procrastination, and denial. These self-parenting strategies by traumatized child parts may alternate back and forth, or berate the psyche simultaneously, activating nervous collapse, depressive states, and anxious overwhelm.

Other times, when these child-parents both lose control, the exiled child escapes from confinement and runs rampage, exhibiting all the qualities originally disowned by the psyche. The exile may also express their terror and distress through dissociation, brain fog, trauma freezing, or other trauma overwhelm symptoms. The child’s exiled qualities will be a combination of constructive and disruptive traits, but the constructive ones will be expressed in raw and undeveloped form due to the lack of nurturance they have received.

Traits like self-confidence, empowered action, boundary-setting, creativity, and boldness are examples of valuable traits that are often consigned to the shadow. These are the types of qualities that need to be suppressed to endure abuse, and when they have been neglected to languish in the psyche’s shadow, they tend to lack functionality, moderation, or proper expression when the shadow-repression mechanisms fail and the exiled self bursts forth. As such, they may express themselves as arrogance, recklessness, rage, selfishness, cruelty, uncontrollable sobbing, screaming, or other explosive qualities.

Contrasted with these ongoing triangulating drama of shadow repression and management, there also exists the archetype I call the orphan at the window. I took this name from classic orphan films such as Oliver!, Annie, and An American Tale, which always feature a scene in which the adorable orphan ventures to the window, gazes out at a distant light and sings a song of earnest sweetness and hope for good and loving parents to reclaim and cherish them. The orphan is charming and agreeable, waits patiently, and practices singing at the window to cultivate their burgeoning narcissistic and codependent processes. It’s all part of a strategy to become so good that their love will be irresistible. The exiled bad object will be finally banished or effectively suppressed. All the harm and abandonment will be undone. Wholeness will finally be achieved through loving reunion with the good parent (or later) with the good partner.

Codependent and Narcissistic Responses to the Bad Object

Both the codependent and the narcissistic processes are attempting to achieve the same result: resolution of the bad object wound by becoming good. They differ from each other in that the codependent process seeks to study, scan, analyze, and internalize the desires of others, and then conform to those desires. By performing for others in this way, the individual has become useful to others, and is fulfilling their duty to do good. Goodness is conceived in terms of service and performance of duty—in terms of prioritizing the needs of others above one’s own. They hope to be rewarded for their efforts with love and acceptance, or at least prevent others from discarding, demeaning, rejecting, and abandoning them.

The narcissistic approach, by contrast, construes goodness in terms of experiencing superiority, power, or admiration. This experience of goodness is pursued by weaving an illusion to live inside of. Through the imagination, they dream up a false self, someone to be admired, someone powerful, someone to look up to, to respect—in extreme cases, to idolize, or to worship. Then they set about convincing themselves and others that the illusion is true. This could take the form of actually achieving things that confer status and admiration, but to the extent that such efforts are not entirely successful (or are wholly unsuccessful), these efforts are supplemented by charm, charisma, confabulations, grand narratives, unrealistic promises, and projections of confidence. Receiving the desired experience of superiority, power, or admiration from these efforts is referred to as narcissistic supply.

In more advanced and malignant narcissistic processes, increasingly extreme measures will be employed when the efforts listed above fail to prop up the illusory image of the false self, produce the needed supply, or at least defend against narcissistic injury (exposure or refutation of the illusion). These efforts may include verbal abuse, outright lies, gaslighting, plays for social dominance, and mortifying, rejecting, or demeaning the other, supplemented by memory-editing and memory-holing. Through an advanced narcissistic process, the memory itself is subject to revision in order to preserve the internal self-admiration and self-supply.

In a psyche fully captured by narcissism, the external world exists as a self-created projection, including all the people in it. It’s as if the mind were operating a world-building computer game. Other people can show up and interact with the narcissist, but they show up as digital avatars in the computer game and interact through that filter. If the other person has said or done things that threaten or undermine the narcissist’s illusory self, those actions and words will be edited out, deleted, or replaced in the computer game with words and actions that fit the needed narrative. The narcissist will continue interacting only with that self-created computer game and the characters in it.

The degree of severity in a narcissistic process will depend on the severity of attachment trauma suffered in childhood, as well as the timing of the injuries. Ego development enters a crucial stage early in life, roughly between the ages of 2-4, when the psyche learns to create and hold the contrasting concepts of self and others. A natural stage of narcissism, or ego-centrism, occurs at this age. The child has learned that other people exist, but has not yet developed the ability to conceive of others in any way other than by projecting their own self onto the other. For instance, a child who loves toy action figures will be able to connect with feelings of love for his mother, but when he learns her birthday is coming up, he will imagine toy action figures to be the best gift he could give her. In his worldview, toy action figures are the best thing going, and his mother deserves the best. He cannot yet conceive that she has tastes of her own, separate from his.

When enmeshment wounds are severe enough at this stage of development, the psyche becomes arrested in the egocentric state, and never fully develops the ability to incorporate reality-testing and hold pictures of others and the external world based on outside information. Due to this, the narcissistic projection process is relied upon—and also because the ego devastation of the bad object wound is so pronounced, it can barely be encountered without total collapse into paroxysms of shame and doom spiraling. The self-created fantasy projections must be relied on entirely.

Those few who become totally arrested at this stage of emotional development are likely to fit criteria for narcissistic personality disorder. Most people, however, do advance past this stage of development—with varying degrees of integrative success in their abilities to view others accurately and with full empathy.

At the codependent stage of emotional development, the power to empathize with others and understand what they want becomes a paramount skill. Those with advanced codependent processes may identify themselves as empathic, or as highly sensitive persons. They have attuned their energy externally, noticing every gesture, every subtext, every sound, every social dynamic—even attuning psychically to pick up additional information that would otherwise be missed. The codependent scans and studies the outside world, perhaps having learned to do this to anticipate the needs and whims of abusive caregivers, perhaps in a desperate attempt to gain love and approval from emotionally neglectful caregivers.

The narcissistic projective process is still available, however, and is still relied upon when useful. It is doubtful to me whether it is even possible to emerge from childhood without at least some level of attachment wounding and fracturing—and without some level of both a narcissistic and a codependent process. These two complementary processes are attempts to cope with attachment trauma and seek wholeness in relation to the bad object fracturing. As a set, they stand in contrast to more direct avoidance processes, which are also universal, and which serve the purpose of coping with the internal emotional and traumatic distress that exists in the body and psyche due to the experience of attachment trauma itself.

Numerous forms of avoidance and denial are available and familiar to all of us. Addictive processes are perhaps the most common and challenging of these. Most addictions stem from the need to escape painful or challenging emotional experiences through numbing or distraction. Acute forms of avoidance can also occur involuntarily through dissociative reactions ranging from brain fog or memory freezing all the way to memory loss and altered states of personality. The sociopathic process is also an avoidance defense that can be activated through dissociation—a person might experience a temporary and involuntary lack of feeling, care, or love as a protection against overwhelming and painful emotional states.

As with narcissistic and codependent processes, the sociopathic process is also present for everyone. It is demonstrated in activities as simple and banal as performing a math calculation. The sociopathic process is simply the abstract quality of mind, divorced from empathy or emotional investment, that interacts with and manipulates objects. The bad object wound is not felt because there is no shame—there are no bad objects, just objects. As with narcissistic personality disorder, when sociopathy, or psychopathy (the terms are not clearly distinguished from each other), manifests as a pervasive and intractable personality state, it represents a developmental injury or impediment that limits the full expression of the psyche in the ability to form healthy, meaningful connections with others (who can only be related to as objects to be manipulated and acted upon).

Avoidance processes can activate in a pervasive way, so as to avoid situations that will produce trauma activation or it can activate with acuity in response to traumatic dysregulation occurring in the present moment. These pervasive avoidance processes can also perform as forms of self-sabotage, perfectionism, or procrastination. This is designed to protect and preserve the individual’s trauma narrative (another internal avoidance device) by recapitulating the experience of failure. The psyche conspires to avoid situations that would challenge the trauma narrative, or by orchestrating disaster when the individual has the chance to disprove the trauma narrative through productive accomplishment. The traumatic experiences of failure are recapitulated, and the bad object trauma narrative is preserved and protected. Ironically, it is actually healing itself that is being avoided, as the experience of healing necessitates full exposure to bad object wound before it is transcended.

In summary, we see a variety of psychological processes at play engaged as avoidance/coping measures in response to chronic emotional and nervous system dysregulation resulting from childhood attachment trauma. These processes are generally working unconsciously in the psyche. Through dedicated self-examination, these unconscious processes can be made conscious, but they do not immediately dissolve when brought into the light of awareness.

The emotional dysregulation and overwhelm remain in place in the psyche and body as a network of trauma gates. Like a network of electric fences, these trauma gates preserve the psyche’s trauma narrative and bad object introject by severely punishing thoughts and actions that threaten to displace this narrative, expel the bad object introject, and reclaim psychological wholeness. The process of healing, by which this narrative, and this elaborate network of intertwined psychological bombs and fences can be dismantled is beyond the scope of this essay, but will be addressed in a follow-up companion piece.

The Iron Triangle of Shame

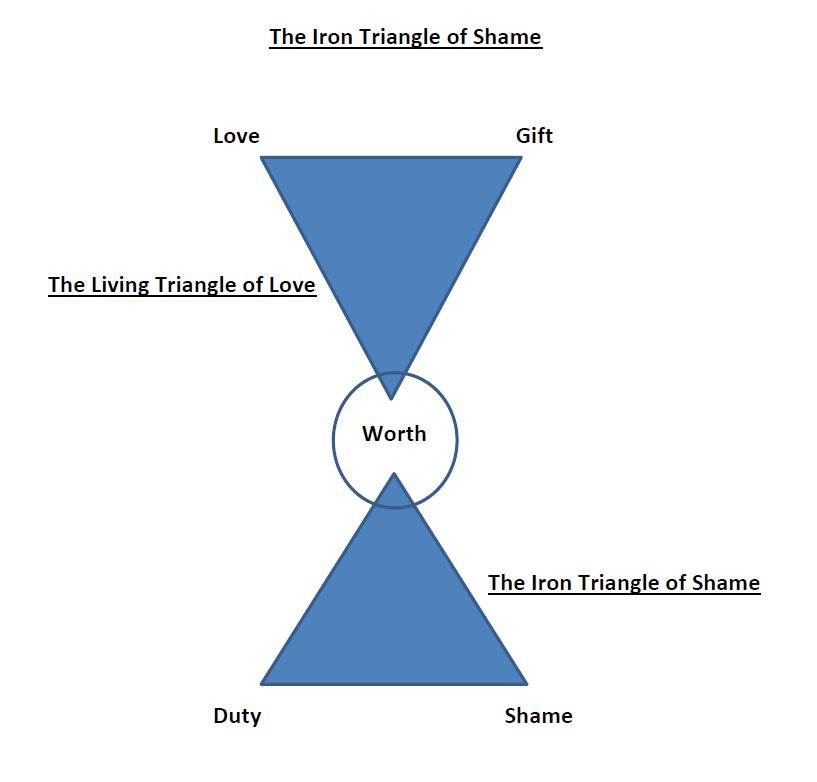

The diagram below details a cyclical pattern I have commonly observed at work in those of us with a fairly well-developed codependent process:

Due to the bad object introject, the psyche attuned to codependent processes is perpetually lodged in the bottom triangle, proceeding clockwise from point to point: from shame to duty, from performing duty to worth, and then bouncing against the glass ceiling of self-worth that can never be attained and proceeding back down to shame. Watch my Psyche and Spirit with Relendra episode on the Iron Triangle of Shame for a deep dive into this process.

In the triangle, shame acts as a kind of fuel, prompting the individual to performance of duty—ultimately some form of service to others. The pain of shame is the motivating vehicle, and duty is the antidote to shame that will provide relief from emotional pain through the achievement of worth. Shame is felt because the codependent individual has not served others enough, has not sufficiently paid back the world for existing. The codependent is always in debt to others and must serve and perform for them.

The catch-22 of the Iron Triangle of Shame occurs when the codependent has sufficiently performed her duty. She approaches the destination of self-worth at the peak of the triangle, and starts to feel proud or self-satisfied. “Maybe I’m good after all,” the codependent thinks. But this thought threatens the trauma narrative that protects the codependent’s bad object introject. “You should be ashamed,” says the introject. “Imagine thinking you’re good. What could be more shameful? If you ever thought you were actually good, you would stop doing your duty and you would just become a selfish, conceited, narcissistic, parasitic burden on the world. You would be the worst of the worst. If you were truly good, you would be ashamed of yourself for even briefly thinking of yourself as good.”

The activation of this narrative script kicks the codependent back into shame—which, from the point of view of the codependent complex, is good! The more shame the better, because there is more fuel for service and performance of duty. Most of the time, the codependent will simply circumvent the whole part of the process which involves briefly feeling good and just stay in a low-grade state of dejected shame while serving and performing duty as a habitual state of being.

Inverse to the Iron Triangle of Shame is a sketch of the process I call the Living Triangle of Love. This is what life can look like when self-worth is no longer the ceiling that can never be breached—it is instead the ground below which one can never fall. From a place of inherent self-worth, the emotional constellation of love is activated, with specific states such as gratitude and appreciation that inspire the individual to take action from a place of gift. Such gifts could take the form of service, or performance of duty—but if so, this arises from an authentic desire to express love by giving to others from love rather than from a place of dejection.

By contrast, the narcissistic process is also characterized by an individual mired in shame below the unattainable sky of self-worth. However, because narcissism works through the projective fantasy function, the narcissist is under the illusory belief that she does experience self-worth. In reality, she is actually mired even deeper in shame than the codependent—a shame so deep and painful it is perilous for the conscious mind to confront it directly.

Because the experience of self-worth is illusory, it is by no means a ground one can never fall beneath. The narcissist requires a never-ending infusion of narcissistic supply to keep from sinking beneath the ground. Whereas the codependent’s conscious experience of shame motivates the performance of duty, the narcissist’s unconscious avoidance of shame requires the seeking of supply. Supply can be attained by the actual accomplishment of some impressive feat or attaining power, or it can be attained by the weaving of projective fantasy narratives in which the impressive feat or power is sure to reach fruition in the near future, or in which the accomplishment of the impressive feat or possession of power is constructed out of whole cloth.

The narcissist need not accomplish anything impressive at all as long as she is able to receive sufficient supply for simply being splendid or admirable as an inherent quality. Utilizing a combination of expressed admiration for intrinsic traits and for external accomplishments, the narcissist will be able to keep her illusory self-worth above the waterline. Supply works best when experienced directly as possessing tangible power relative to others. Second best is to receive praise and admiration from others. If these preferred sources of supply fail, the narcissist can make do for a while by utilizing self-supply (that is, self-admiration) through internally reinforced narratives.

I have been referring to the narcissist and the codependent for ease of reference, but in actuality (as mentioned earlier) I am presenting narcissism and codependency as processes that exist in all of us to some degree—with each process expressed on a spectrum of intensity unique to each individual—and which fluctuates in intensity at different stages of life and in response to the stressors and challenges of circumstance. Indeed, a person with a long history of cycling through the codependency of the iron triangle of shame may attempt to break through the glass ceiling of self-worth by leaving codependency behind entirely and leaning into a narcissistic process of fantasy. The codependent wills himself into self-worth through self-supply and breaks through the ceiling.

It may even seem authentic and genuine for awhile. The codependent is using the projective function to weave a narrative in which it’s okay to feel good about himself. But since the fracturing of the bad object introject has not actually been healed, but simply patched over with narcissistic supply, it is only a matter of time before the house of cards comes tumbling down (unless he can obtain enough supply to remain in a narcissistic state of illusory self-worth perpetually).

I have theorized that what is often termed borderline personality disorder can be characterized as the cyclical process of a person with a very pronounced bad object wound flipping between narcissistic and codependent strategies for coping, neither of which are able to stay in place for long. The chaos and emotional turmoil associated with a borderline personality process is the result of the disruptions caused by flipping between these two processes and the debilitating exposure to an extremely painful bad object introject on a repeated basis.

Another phenomenon that can sometimes be observed is the meeting place where the narcissistic and codependent processes overlap and resemble each other. This is accomplished when a narcissist latches onto service, or performance of duty as his source of supply. The narcissist could also gain an experience of power by piously serving others, placing others in his debt and achieving moral superiority. Or he could capitalize on his failures by utilizing the dejected persona of codependency in conjunction with a victim narrative to gain power over others from below.

Alternatively, the meeting place could be reached when the codependent attempts to break through the self-worth ceiling by realizing she can utilize the performance of duty function she’s so familiar with as a life raft of supply to keep her afloat (directly mirroring the narcissist strategy of gaining admiration from others through self-sacrifice and dedication). In either case, it is possible for admiration-seeking activities and to be recharacterized as activities done for the purpose of serving others in the interchangeable narcissist/codependent internal narrative. The merged codependent/narcissist can convince herself that activities performed for the purpose of self-aggrandizement are actually helpful to others and in service of their needs.

This results in a less explosive dynamic than the previously described borderline process since stability is generated by merging the codependent and narcissistic processes and there is no need to flip back and forth. It is however, just as susceptible to the debilitating onset of overwhelming shame. Instances are bound to recur when the internal narrative breaks apart and the raw, direct experience of the bad object once again assaults the psyche, emotions, and nervous system.

Symbiosis of the Narcissistic and Codependent Process

Most often, a person’s narcissistic and codependent processes will not be equally expressed, but one process will be a dominant function and the other an inferior function. In such cases, the illusion of wholeness can temporarily be achieved by finding an intimate partner whose dominant process is an inverse match to one’s own dominant process. Codependency and Narcissism fit together like an hand and glove. The person in the role of the narcissist requires supply, and this perfectly matches the needs of the person enacting the codependent role, who is looking for ways to provide service to another.

The codependent and narcissist create a shared fantasy together. The narcissist creates the fantasy and the codependent populates it, fleshing it out, making it feel and appear more real. A good metaphor for this is to perceive the narcissist as the director, writer or producer of a film, whereas the codependent is the star actor cast in a lead role. The narcissist’s projective power creates the vision for the shared fantasy, and the codependent is only too happy to receive the script, rehearse her lines, and become the living embodiment of the narcissist’s vision.

They are both unconscious of what they are doing, or why they are attracted to each other. The narcissist soon tires of the codependent. The continual need for supply requires the famous film director to continually outdo himself and top his previous magnum opus; to do so, he needs to work with fresh talent. Meanwhile, the codependent wonders why she keeps pairing up with abusive directors who treat her like gold at first, but inevitably come to devalue and discard her.

Whether one leans heavily toward a codependent or narcissistic process, or the two processes are relatively equal in strength—in merged form, or flipping back and forth from one to another—whether one seeks a mirror process from an intimate partner to enact the shared fantasy drama, or enacts the process internally in solitude—the processes cannot resolve without addressing and healing the enmeshment wounds, attachment fracturing, and bad object introjects at the root of both processes.

Having mapped out the territory of attachment trauma and its effects, the subject of healing will be addressed in a subsequent essay.

The information contained in this article is summarized in outline form below for those who wish for a more succinct reference guide

Narcissism, Codependency, and Avoidance Part One: The Foundations of Attachment Trauma

Foundations:

Narcissistic Process

· Projective Function of the Psyche (imaginative, visioning, fantasy, dreaming, creative)

· Projects judgments, values, beliefs, and goals onto and into others

· Preference for Projective fantasy rather than externally validated realities

· Defends against external inconsistency by editing reality, deleting memories, and creating new projections

Codependent Process

· Introjective Function of the Psyche (internalizes external judgments, values, beliefs, and goals)

· Sense of self is externally determined

· Internalized negative self-concept, resistant to contrary evidence

· Vulnerable to gaslighting and self-doubt

Avoidance

· Shields the psyche from emotional distress or overwhelm

· Conscious and Unconscious

· Addiction and Addictive Processes

· Regulates, emotions through soothing or numbing

· Unconscious Avoidance: (dissociation, brain fog, memory lapses, nervous collapse, blocked memories)

· Maintenance of trauma narratives through self-sabotage, addiction, and avoidance of reparative experiences

Formation of Narcissistic and Codependent Processes

Attachment trauma

· Can be referred to as attachment wounding or enmeshment wounding

· The psychological injuries suffered in childhood, mainly from primary caregivers, but also with siblings and other family members, authority figures outside of the home (such as teachers), or from peers through bullying or other forms of abuse.

Enmeshment

· Overlap (or total lack) of boundaries between the child and (usually) a primary caregiver (or between adults later in life)

· Creates confusion and overwhelm in the child’s psyche regarding sense of self and others, between love and abuse

· Creates an introject that carries the “You are bad” message (the bad object introject)

Fracturing

· Splits the self-affirming state of the psyche (the true self) against itself

· Child internalizes enmeshment wounds and blames self for them

· Child is split between self-love and rejection of self as the bad object

Bad Object Introject

· Term used to describe the rejected or exiled part of self created by enmeshment wounding and fracturing

· Becomes confused with child’s own sense of self

· By seeing self as the bad object, the child protects the positive image of the abusive, neglectful, or otherwise enmeshed caregiver

Types of Enmeshment Wounding

· Dissonance between internalized bad object and true self generates shame

· Abuse and neglect are the primary types of enmeshment wounding

· Projecting false identities onto a child is also an enmeshment wound

· Can be summarized as any instance in which the child is utilized as an object in service of the primary caregiver’s needs

· Emotional neglect is amplified by its invisibility and the message of the introject it creates: “I don’t matter at all. I don’t even exist.”

· Inaccurate Mirroring occurs when the parent imposes identity projections onto the child or simply ignores the child

· Gaslighting is another term for inaccurate mirroring, summarized as the imposition of an identity or internal truth onto another that contradicts that person’s own identity or internal truth.

· Conditional Love occurs when the parent withdraws affection to punish the child for not conforming to the parent’s desires, or withholds affection as a baseline and bestows scarce glimmers of affection to reward the child for compliance.

· Physical abuse imposes harm on the child’s body, or violates the child’s body and boundaries

· Sexual Abuse is physical abuse with added overwhelming and compounded boundary violations and enmeshment confusion. It is typically the most profound type of enmeshment wound that can occur.

· Verbal abuse constitutes an extreme form of gaslighting in which the child is disparaged and shamed with devaluing projections.

· Imposition of Chaos leads to confusion, chronic states of fear, and learned helplessness in the child

· Parentification of a child occurs when a child is required to attend to and caretake the parent’s emotional or material needs in a direct way

· The creation of a parentified child can be understood as a component of all attachment trauma to some degree.

Anatomy of the Fractured Self

· The Exile, or Shadow. The part of self identified with the bad object introject

· Strict Parent. Permutation of the parentified child that is harsh, punishing, critical, and unforgiving

· Permissive Parent. Permutation of the parentified child that is neglectful, chaotic, and indulgent

· These permutations of the parentified child attempt to manage or mollify the exiled part

· Orphan at the window is the child part faithfully longing for parents to truly see and love the child, or for a surrogate parent (in role perhaps to be played by intimate partner) to do so. The orphan child will attempt to win over the parent or surrogate parent by exhibiting only good qualities and either excising the bad object exiled self entirely, or by sufficiently repressing the exile enough to be worthy of love.

Codependent and Narcissistic Responses to the Bad Object

Narcissistic Projective Process

· Resolution of the bad object wound by becoming good through construction of a false self

· The goodness of the false self is construed in terms of superiority, power, or admiration.

· Narcissistic supply refers to the narcissist’s experiences of admiration, power, domination, veneration, praise, and so forth

· Supply is pursued through fantasy projection, psychological influence, and achievement of admired feats

· Narcissistic Injury refers to the exposure or refutation of the illusionary false self

· In a narcissistic process, abusive or otherwise aggressive tactics will be used to defend against narcissistic injury or counterattack when the injury has already occurred

Attachment Trauma Affecting Ego Development

· Ego development is arrested by attachment trauma, which interferes with the ability to differentiate between self and others and to accurately identify authentic internal desires and aversions

· Attachment trauma occurring earlier in development can arrest the ego in a state of egocentrism—the narcissistic process of projecting one’s own reality onto others and failing to differentiate between the two

· Severity of the bad object wound is also a factor in development of the narcissistic personality process. The more severe the wound, the greater the need to avoid the wound entirely though narcissistic projection

Codependent Process of Service and Performance of duties

· Alternative strategy to becoming good and resolving the bad object wound

· Goodness is defined according the external needs and desires of others, and the usefulness of the codependent relative to these

· The codependent process seeks to study, scan, and internalize the desires of others

· The codependent takes action in service of others, through performance of duty, and hopes to earn goodness, self-worth, and love as a result—or at least not be rejected and abandoned

· Empathy and sensitivity become highly developed to accomplish these goals and avoid abuse

Avoidance Processes

· Narcissism and codependency can both be understood as avoidance processes—they represent ways of approaching interpersonal relationships while managing attachment trauma and fracturing from the bad object wound

· Other avoidance processes are engaged to deal with the symptoms of attachment trauma itself, such as dissociative reactions, memory lapses, or addictive processes

· The sociopathic process numbs the emotions entirely. It blocks out the bad object wound because there are no bad objects, just objects

· Avoidance processes can also take the form of self sabotage, perfectionism, or procrastination—methods by which traumatic experiences of failure are recapitulated, and the bad object trauma narrative is preserved and protected.

· Avoidance processes largely operate unconsciously. When brought to consciousness, the physical experience of emotional overwhelm continues to present a challenge in healing attachment fracturing and resolving the wound of the bad object introject

The Iron Triangle of Shame

Codependent Process

· For the codependent, shame provokes the performance of duty to alleviate shame and achieve worth

· Achieving worth activates feelings of shame, since the motivation to do good through service and performance would be absent without the experience of shame or the threat of shame

· The experience of shame undermines the feeling of worth achieved through duty, and the cycle repeats

Narcissistic Process

· The illusion that self-worth has already been achieved is sustained through the projective fantasy process

· To keep the illusion in place, the narcissistic process requires constant access to supply. Supply is sought through self-aggrandizing achievements or by eliciting supply from others through charisma or other projections of the false self that do not rely on actual accomplishments

Codependent and Narcissistic Overlap

· The codependent may attempt to break free from the iron triangle of shame by utilizing a narcissistic fantasy process to burst through the ceiling of self-worth

· The narcissist may attempt to utilize the codependent process of service and performance of duty to win supply in the form of admiration from others (and self-admiration).

· The merger of codependent and narcissistic processes is more stable than flipping back and forth between them, but is ultimately no less precarious.

Symbiosis of the Narcissistic and Codependent Process

· For people suffering from chronic attachment trauma wounding, intimate partnership will likely result in which one partner plays the narcissist for the benefit of the other’s codependent, and vice versa.

· The narcissistic process is seeking supply, and the codependent process is seeking to serve the needs of others. If both parties can accomplish these aims together, they can ward off the emotional pain of their bad object introjects together as well.

· The symbiosis of these two processes can be characterized as the formation of a shared fantasy, with the narcissist in the role of the director and the codependent in the role of the star actor.

Another great article, thanks. Having emerged in 2020 from an abusive ten-year relationship, I can see how we exemplified the codependent and narcissistic dynamics you describe. I was the codependent one, always trying to do my duty better than before, in the hopes of avoiding future criticism and abuse.

Since I left, my ex has been working almost continuously on the "accomplishment of some impressive feat", like hiking the Continental Divide Trail (3000 miles), or skiing the Catamount Trail (300 miles), to name just a few of the things she's done.These feats really are impressive, and they're a continuation of the things she did in her 20s, like hiking the AT (twice) and the PCT. But these feats also seem like an attempt to regain a sense of self-worth that is severely wounded.