The search for clarity and truth in the assassination of President Kennedy benefits from a methodical process of identifying key narrative inflection points in the case and employing narrative frame comparison to test each of the narrative frameworks that follow from these inflection points. This process was initiated in the first part of this article, The JFK Assassination: What Didn’t Happen, Part One.

The first important narrative inflection point in the case is the classic divide between two narrative frame perspectives:

1. Kennedy was fired upon by multiple gunmen.

2. Kennedy was fired upon by a single gunman.

The first frame can only be true if a plot existed to assassinate Kennedy. If so, it will become important to identify how big the plot was, which actors were members of the plot, what their motives were, and whether the Federal Government failed to reach this conclusion through simple negligence and incompetence, or actively covered up for the killers. If they were active in a cover up, their motives for doing so must be explored.

If the second frame is true, the single gunman who fired at Kennedy could have been acting alone, but he still could have been acting as a member of a plot. If he acted alone, there is little more to examine in the case. If he was a member of a plot, the same questions raised in the first frame still apply.

Part one of this article summarized the ballistic and medical evidence in the case. Strong evidence demonstrates that multiple gunmen fired upon Kennedy—but if this is true, it is also true that evidence was suppressed, misrepresented, and even altered by official institutional actors investigating the case. These actors would include members of the FBI and the Warren Commission, and participants in President Kennedy’s autopsy.

In order to reject the medical and ballistic evidence supporting multiple shooters, it is necessary to reject the testimony of at least 80 witnesses, including the corroborated testimony of over 20 medical doctors. It is necessary to support the Single Bullet Theory, including impossible trajectories in the path of the single bullet—both through the air and through President Kennedy’s body.

It is also necessary to believe this bullet suffered almost no damage in causing seven wounds in Kennedy and Governor Connally. It must be believed that this bullet lost less weight in causing those wounds than the weight of the bullet fragments found in Connally’s body as a result of these wounds. It is also necessary to disbelieve visual evidence in the Zapruder film that shows Kennedy and Governor Connally were initially hit by separate bullets, and after this, Kennedy was struck by a bullet from the front, shoving his body violently backwards.

The Lone Gunman theory of the case argues that as implausible as it might seem, the beliefs summarized above are not actually impossible. Official experts are on record insisting they are indeed possible. Not only is it possible that Kennedy was fired upon from behind by a single shooter, this is in fact what happened.

As best as I can tell, the reason Lone Gunman proponents believe these things can be summarized as follows: They believe the case against Oswald is overwhelming, and they believe the level of official corruption required for the veracity of the Multiple Gunman interpretation is not believable. If these two things are believed strongly enough, the implausible beliefs required by the Lone Gunman theory seem less implausible than the alternative. This dynamic, combined with the phenomenon of expert foreclosure, creates an impasse in the process of eliminating impossibilities in a narrative frame comparison.

To break this impasse, the first strongly-held belief of the Lone Gunman perspective must be addressed. If it can be shown that Lee Harvey Oswald could not have killed Kennedy—and if this can be done without relying on evidence that requires expert interpretation—disbelief in the possibility of endemic official corruption can also be broken. The best way to do this is through concrete corroboration: evidence constrained and corroborated by known facts that are time and place specific.

The Case Against Oswald

What then, is the basis for the case against Oswald? In part one of this article, I explained that the official case narrative is built around the Mannlicher Carcano rifle claimed by Dallas Police to have been found on the 6th floor of the Texas School Book Depository (TSBD) building, along with three spent shell casings. The FBI claimed to have retrieved microfilm from Klein’s Sporting Goods on November 23. The microfilm contained an image of an order form for this type of rifle and an accompanying envelope, both bearing the post office box address Oswald was using at the time the order was made. The rifle was ordered in the name of “A Hidell,” said to be an alias used by Oswald (as supported by other evidence in the case). By ordering the rifle through the mail, Oswald conveniently left a paper trail linking him to it, rather than buying a rifle in person at a local Dallas gun shop, which would have left no paper trail.

The other key points of evidence against Oswald include the testimony of Oswald’s coworker Buell Wesley Frazier and Frazier’s sister, Linnie Mae Randle. They claimed Oswald brought an oblong package to work the morning of the assassination, said by Oswald to contain curtain rods. The Dallas Police Department (DPD) claimed to have discovered a paper bag on the 6th floor used by Oswald to carry the rifle to work (under the guise of carrying curtain rods). The FBI later identified prints from Oswald’s right palm and left index finger on the bag. The DPD also belatedly claimed to have identified Oswald’s palm print on the underside of the rifle barrel, a part of the rifle that is only exposed when in its disassembled state.

Boxes stacked next to the 6th floor window also bore Oswald’s fingerprints. One of these prints was detected through use of fingerprint powder by the DPD, indicating Oswald had touched the box sometime in the previous three days. The other prints were detected only through FBI chemical analysis, meaning they could have been on the boxes for longer than three days. Since Oswald worked on that floor and handled boxes as part of his work duties, these prints do not constitute evidence of Oswald shooting Kennedy. If the other evidence in the case is not able to incriminate Oswald, the prints on the boxes would certainly not be sufficient to do so on their own. If the other evidence in the case is enough to incriminate Oswald, the prints on the boxes are superfluous.

Only one witness, Howard Brennan, ever claimed to have seen Oswald at the southeast corner window of the TSBD (where the shell casings were found). But on the day of the assassination, he was taken to a police lineup that included Oswald and did not identify him as the man he saw shooting a rifle from that window—even though Brennan had already seen images of Oswald on television as the arrested suspect. He also described the shooter as wearing a light-colored shirt and trousers of a similar color. Oswald had worn grey trousers and a reddish shirt (sometimes described as reddish-brown or maroon) over a tee shirt to work that day.

Brennan did not identify Oswald as the shooter until he sat for an FBI interview on December 17th. Brennan then retracted this identification in a subsequent FBI interview on January 7. Brennan later retracted this retraction and again identified Oswald in his Warren Commission testimony, claiming that he could have identified Oswald when he saw him in the police lineup, but didn’t.

At the time of the shooting or in the minutes leading up to it, one other witness observed a man in the 6th floor corner window with a rifle, but could not describe the appearance of the man or his clothing, other than to claim he had a bald spot (unlike Oswald). Two other witnesses observed a man in that window, but did not observe a rifle. Like Brennan, they both described the man as wearing a white or light-colored shirt, but both specified that it was an open-neck shirt, not a tee shirt.

Numerous other witnesses reported observing a man through a window on the upper floors of the TSBD, often accompanied by another man, and often with a rifle. The floor number and window locations cited by these witnesses varies. None of these witness observations comport with the Oswald-as-Lone-Gunman theory of the case. These reports do raise important questions about the actual location of the TSBD gunman, whether that gunman was accompanied by a second man, and whether multiple gunmen may have been present at separate locations in the building.

Early press reports are consistent with the possibility that multiple weapons were found in the TSBD. In the hours after the shooting, the first report claimed police had found a .303 British Enfield. After this, the press reported that police had found a 7.65 Mauser as reflected in the report of Deputy Sheriff Boone and the sworn affidavit of Deputy Sheriff Weitzman, who were both present when the rifle was found. Dallas law enforcement and the press continued to describe the rifle as a Mauser until the following day, when the rifle started being described as a 6.5 Mannlicher Carcano. Early reported locations of where the rifles were found included the 5th floor stairwell, the roof, and the 6th floor.

Howard Brennan’s belated and inconsistent identification of Oswald lacks credibility due to the discrepancy in clothing and his failure to identify Oswald at the police lineup just hours after the assassination. None of the other witnesses referenced above ever identified the man they saw (or either of the two men they saw) as Oswald. No witnesses from inside the building ever saw Oswald carrying a package to work that morning (including Jack Dougherty, who saw Oswald enter the building), nor did anyone see him carry a package up to the 6th floor.

Several coworkers testified to seeing Oswald on the 1st floor starting at the beginning of the lunch hour, at times ranging from 11:50–12:00pm. In the FBI’s summary of coworker Carolyn Arnold’s statement, she claims to have glimpsed Oswald on the first floor as she was leaving the TSBD to watch the motorcade. They listed the time of this incident as occurring between 12:00pm–12:15pm. Arnold later corrected the record personally, stating she left the building at about 12:25pm. Years later, in a 1978 interview, Arnold stated she had actually seen Oswald in the 2nd floor lunchroom as she was leaving her 2nd floor office on her way to the front steps. A coworker who left the office with Arnold verified 12:15pm as the time they left the second floor.

As shall be seen, Oswald claimed he went to the 2nd floor lunchroom to buy a coke from the vending machine prior to eating his lunch on the first floor. This lines up with Arnold having seen Oswald on the second floor at 12:15pm. It is unclear whether Arnold saw Oswald in both places (the 2nd floor lunchroom, and at the front door of the building) at both times (12:15pm, and 12:25pm), or whether she only saw him in one of those locations at one of those times. Either way, she was consistent in her insistence that she saw him on the lower floors during this time frame. Kennedy was shot at 12:30pm.

The remainder of the evidence meant to implicate Oswald is circumstantial: allegations that he attempted to assassinate General Edwin Walker on April 10, 1963, allegations that he murdered Dallas police officer JD Tippit following the Kennedy assassination on November 22, and the backyard photos showing him brandishing communist newspapers and a rifle. Even if the first two allegations were true (strong evidence indicates neither of them were true), and even if the backyard photos were authentic (strong evidence indicates they were not), they would not establish Oswald’s guilt as Kennedy’s assassin without evidence tying Oswald to the Mannlicher Carcano rifle at the 6th floor window of the TSBD at 12:30pm on November 22, 1963.

In JFK and the Doorways to Perception, Part 2, I demonstrated why the backyard photos must have been forgeries created to assist in the framing of Oswald. If so, not only are these photographs incapable of establishing Oswald’s guilt in President Kennedy’s death, they ironically weaken the case against him.

Let us examine the evidence placing the rifle in Oswald’s hands and the evidence placing Oswald at the window. In both instances, I will show that neither evidentiary conclusion can be established. More important, I will show that both evidentiary conclusions can be eliminated as impossible. This will be done through concrete corroboration

Oswald and the Rifle

The strongest evidence that breaks the link between Oswald and the Mannlicher Carcano rifle is the documentation used by the FBI to establish that Oswald ordered the rifle from Klein’s Sporting Goods on March 12, 1963. This documentation was methodically analyzed by researcher John Armstrong, and the results of this research conclusively establish that Oswald could not have received the rifle. This evidence is extensive and can be viewed in detail on Armstrong’s website. I will summarize Armstrong’s most important findings and direct the reader to follow the preceding link for verification.

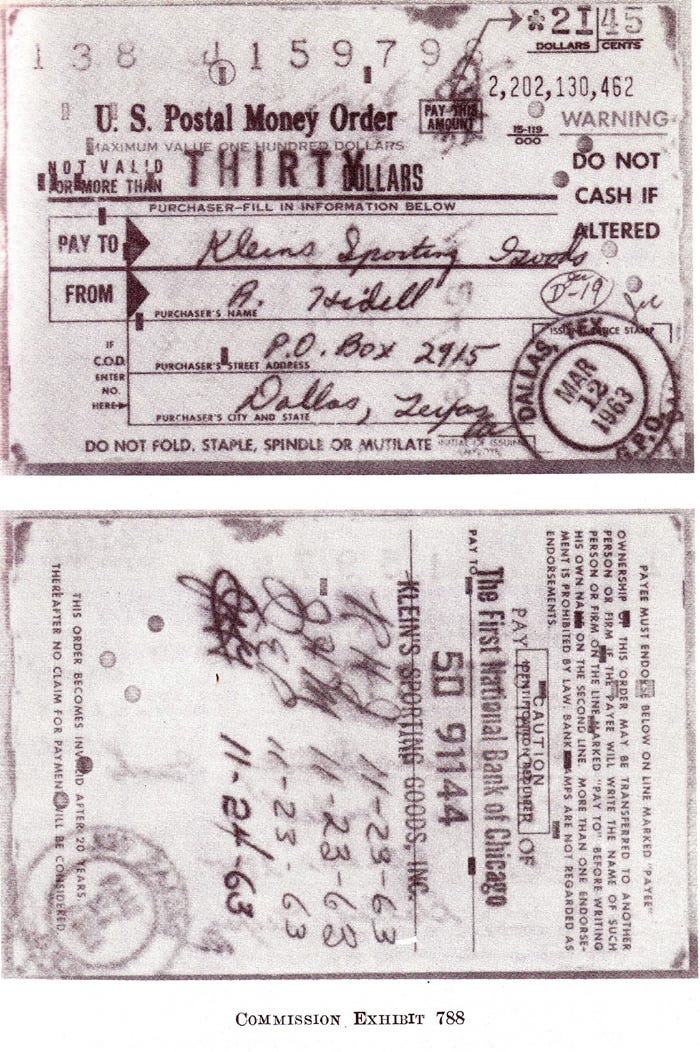

The FBI submitted photographs of the $21.45 money order shown above into evidence in the case against Oswald. It was supposedly purchased by Oswald on March 12 to render payment for the rifle. The FBI claimed the money order was located and retrieved from the Federal Records Center in Alexandria, Virginia. This money order bears a stamp indicating its purchase date and it bears an endorsement stamp from Klein’s. If it had been deposited, it would have been stamped by the receiving bank, then sent to the Federal Reserve and stamped by them, and finally sent to the postal processing center in Kansas City where it would also receive a stamp. The absence of a single stamp from any of these institutions reveals that this money order was never deposited.

The March 12, 1963 money order stamp also bore the words DALLAS, TEX G.P.O., the stamping insignia used by the Dallas General Post Office. This post office was located half a mile away from Oswald’s place of employment at the time: Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall. The mailing envelope accompanying the order form for the rifle bore a stamp postmarked at 10:30am, March 12, and bore a “12” instead of “G.P.O.” This insignia shows that the envelope was mailed from postal zone 12. The nearest zone 12 mailbox was 2.5 miles west of the General Post Office.

Records at Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall contained time sheets showing Oswald’s activities working continually on 9 successive camera jobs from 8:00am–12:15pm on March 12. The time spent on each job is delineated in these records showing no gaps in time between projects. For Oswald to have purchased the money order and mailed the order form that morning, he would have to have been missing from work for a considerable length of time and fabricated his time sheet with no one noticing. Bizarrely, he would also have to have chosen to mail the envelope 2.5 miles away from the post office where he purchased the money order—rather than simply mailing the envelope from the post office he was already at. Oswald did not drive or own a car, making this sequence of events even stranger and more difficult for Oswald to have achieved.

When the FBI asked Klein’s to produce documentation showing the $21.45 deposit from their records, they complied, producing a typed summary document for a $13,827.98 daily deposit with $21.45 as one of the amounts listed in that deposit. The document bore the date of March 13, written in pen. Klein’s also produced a deposit slip for $13.827.98, but this slip was dated February 15, 1963. The second of these dates is not a possible deposit date for the March 12 money order for obvious reasons. The date of March 13 is also not plausible; it would have taken longer than one day for an envelope mailed in Dallas, Texas to reach Klein’s Sporting Goods in Chicago. Images of the deposit summary document and deposit slip are shown below:

The likely explanation is that Klein’s deposit summary document was actually from February 15—as verified by the deposit slip—and March 13 was written on the document in pen to fabricate evidence of the money order’s deposit. In a sloppy oversight, the date of March 13 was chosen instead of the 14th or 15th, which would have allowed an extra day or two for the order form to arrive in the mail. But if one successfully passes off a February 15 deposit slip as evidence that a March 12 money order was deposited, it doesn’t matter much if the March 13 date is also flubbed. The FBI and Warren Commission were just as willing to ignore these glaring date discrepancies as they were to ignore the never-deposited status of the money order itself.

On top of all this, postal regulations required any firearms sent by mail to be documented by form 2162, which the post office was required to retain for four years. The shipper and receiver of the firearm both had to fill out and sign this form and copies were retained by both parties. No copies of form 2162 were ever located or entered into the record. What’s more, the Dallas Post Office had no records indicating A. Hidell was authorized to receive mail at Oswald’s PO box.

US Postal Inspector Harry Holmes had been monitoring Oswald’s mail at the time, and he forwarded the information he found to the FBI. For instance, he notified the FBI when Oswald first sent a letter to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. With this level of monitoring in place, neither Holmes nor any other postal employee had any memory or record of Oswald receiving a package that could have contained the rifle. As a final icing on the cake, the order form for the rifle corresponded to a 36-inch Carcano, but the assassination rifle in evidence was a 40-inch model.

The documentation purporting to show that Oswald ordered the assassination rifle shows that Klein’s Sporting Goods never deposited a money order for the rifle. Instead of incriminating Oswald, the documentation actually shows that the FBI collected and submitted manufactured evidence against Oswald. It also shows that the Warren Commission accepted this false evidence. Unlike the medical and ballistic evidence, or the backyard photos, this evidence is not subject to expert interpretation. It constitutes concrete corroboration that Oswald was framed.

The image of the order form and envelope sent by Oswald was supposed to have originated from Klein’s microfilm records. This microfilm disappeared from its cannister in FBI archives and was never able to be verified by a third party. Only the FBI photographs (purportedly from the microfilm) showing the order form and the envelope survived. As such, no direct evidence shows these documents ever existed on the microfilm in the first place. They might have existed—and they might have been fabricated. We just don't know. Neither does any evidence exist showing that Oswald received the rifle from his PO box. This lack of evidence would be expected, since Klein’s would not have shipped a rifle without receiving and depositing payment for it.

Instead of evidence tying Oswald to the rifle, we see evidence of a fabricated paper trail, replete with mistakes: an envelope bearing a postmark from a different postal zone than that of the money order, an order form for a rifle of the wrong length (made out in the name of a person not authorized to receive mail from the PO box to be shipped to), a money order that could never have been deposited, and two documents with conflicting dates purporting to show that it was deposited. One of these dates occurred several weeks before the money order was supposedly issued, and the other date occurred too early for the money order to be shipped, received, and processed.

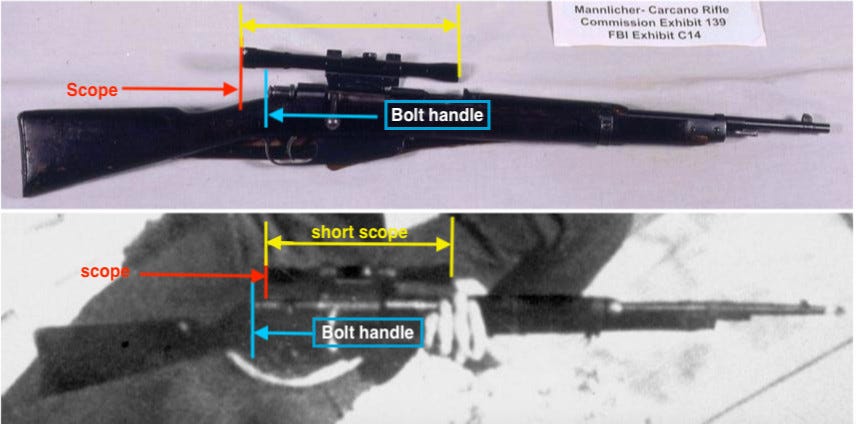

The backyard photos contain an additional mistake in the evidence used to tie the rifle to Oswald. According to the Lone Gunman narrative, the backyard photos were taken on March 31, 1963, shortly after Oswald received the rifle in the mail from Klein’s. But take a look at the comparison photos below (with thanks to David Josephs for posting these in the JFK Assassination Education Forum). A photo of the rifle in evidence is pictured on top, and an image of the backyard photo rifle is beneath it:

The comparison image above clearly shows these to be different rifles. Comparison point 3 is most easily identifiable in its stark variance between the two rifles. A second comparison photo, shown below, shows that the scope on the backyard photo rifle is significantly shorter than that of the rifle in evidence:

Evidence of forgery in the backyard photos demonstrates that Oswald was framed for Kennedy’s murder ahead of time (see JFK and the Doorways to Perception, Part Two), but it also constitutes further evidence that Oswald did not order the Mannlicher Carcano found at the TSBD—even if the photos are accepted as legitimate.

Even if Oswald did not actually order the rifle from Klein’s, it could still be argued that Oswald acquired the rifle by other means. Perhaps the FBI framed him for ordering it just to strengthen their case against him. Therefore, the evidence of Oswald’s palm and fingerprints on the bag and the rifle must also be examined.

The Fingerprints and the Bag

Lieutenant Day of the Dallas Police Department (DPD) initially identified traces of fingerprints on the rifle near the trigger, photographed them, and wrapped the area with protective cellophane, following standard procedure. The next day, the DPD shipped the rifle to the FBI in Washington DC along with the other physical evidence in the case. FBI fingerprint expert Agent Latona examined these fingerprint traces as well as the rest of the rifle and found no identifiable prints. Six days later on November 29, the FBI in Washington received a card from the DPD bearing a palm print matching Oswald’s right palm. An inscription on the card stated the print was lifted from the underside of the gun barrel. Agent Latona determined the rifle bore no evidence consistent with a print having been lifted from the barrel.

Lieutenant Day went on to claim he actually lifted the palm print on November 22 using adhesive tape, but he neglected to take any photographs proving he had done so, neglected to wrap the area in cellophane, and neglected to mention to the FBI that he had retrieved this print. Day claimed he thought the FBI would find it themselves, so he didn’t bother to tell them. His explanation for why he never photographed the print and did not cover it in cellophane was that he did not have enough time to do so. It is unclear why he waited for days to send the palm print card to the FBI rather than sending it with the rest of the evidence.

This palm print would have been the only direct physical evidence linking the suspect to the murder weapon in the crime of the century. Day’s lackadaisical attitude toward standard procedure with this piece of evidence is not believable. Neither is his withered excuse that the FBI would probably find the print themselves (which of course, they didn’t, because it wasn’t there), and he therefore saw no need to inform them about it. No chain of evidence establishes the origin of the palm print displayed on the card. The evidence shows only that the DPD obtained Oswald’s palm print somehow and placed it on a card. If this evidence points to anything, it points to the likelihood that the print’s origin was fabricated after the fact—another instance of law enforcement attempting to frame Oswald.

The evidentiary circumstances of the paper bag said to have contained the rifle is almost as bad. As with the palm print, no photographs of the bag were ever taken at the time and place of its supposed discovery. Although the DPD claimed the bag was found near the same 6th floor window where the shell casings were found, none of the DPD photographs taken of this area show the bag. Instead, the Warren Commission brazenly resorted to presenting a photograph of the crime scene featuring a drawn outline where the bag was supposed to have been found. The earliest photograph of the bag was taken by the press at about 3pm as Police Detective Montgomery was carrying the bag out the front door of the TSBD.

Each of the officers who were present at the window before the bag was supposed to have been found claimed they did not see a bag there at all. Detectives and officers who later arrived on the scene made conflicting claims about who discovered the bag. Its discovery was variously attributed to four different law enforcement personnel, including Lieutenant Day. There is no coherent narrative about when this bag was found or by whom. All we know about it for sure is that it was removed from the building by Detective Montgomery at about 3pm and had somehow come into possession of the police before that.

The bag was constructed from sturdy paper held together by tape. The FBI conducted laboratory tests on these elements and compared them to samples of wrapping paper used by the TSBD in preparing shipments, and to samples of tape from a stationary TSBD tape dispensing machine. These samples were obtained and provided by the DPD. The FBI concluded the paper and tape from the bag matched the paper and tape from the comparison samples. The TSBD tape dispensing machine leaves distinct markings on the tape when it moistens and dispenses it. Because the bag in evidence bore these markings on the tape holding it together, the FBI concluded the tape must have been applied to the paper at the TSBD.

Troy West, the TSBD employee in charge of the wrapping paper and dispensing machine, testified that his work duties required him to be stationed at the shipping station his entire work day. He even spent his lunch break at the shipping station, including on the day of the Kennedy Assassination. West further testified that he never saw Lee Harvey Oswald acquire paper and tape from the shipping station. No other witnesses ever testified to seeing Oswald retrieve paper and tape from the shipping station either.

In contrast, the record verifies that Lieutenant Day and Detective Studebaker did approach the shipping station and requisitioned several samples of the paper and tape from it. This occurred prior to the bag’s departure from the building at 3pm. Day later claimed this was done to collect samples of the tape and paper for comparison to paper and tape the bag was made from (as the FBI later did). But he doesn’t explain why he expected the bag to have been constructed from TSBD materials in the first place—it’s not an obvious inference to make.

Another possibility is that Studebaker or Day constructed this bag at the shipping station. They might have done so to fabricate evidence that could account for how the rifle was smuggled into the building without being seen. Or they might have done so to protect or conceal other evidence as it departed the building. A photograph of Detective Montgomery carrying the bag out of the building is shown below:

It is clear from the photo that a long object is inside the bag, maintaining the bag’s upright position as Montgomery carries it. It’s anybody’s guess as to what that object is. If multiple rifles were found in the TSBD, this would be one way to get one of them out without it being seen.

This is speculation, of course. Perhaps the bag is being carried out by means of an innocuous object. But with a broken chain of evidence on the finding of the bag, we are left to speculate as to its origins and purpose. The DPD could have constructed it, they could have found it somewhere in the building, or they could have found it exactly where they said they found it. The final option is least likely, given its glaring absence in photos taken of the crime scene and conflicting accounts about who found it or whether it was there at all.

The FBI examination of the bag found no scratches, markings, or creases on the bag consistent with it ever containing a rifle. The Mannlicher Carcano was found in a well-oiled condition and would be expected to leave traces of lubricant on the bag—especially since the bag was not long enough to hold the rifle unless it was in a disassembled state. No traces of lubricant were found anywhere on the bag.

Finally, Buell Frazier, who claimed Oswald brought a package to work that morning, insisted the bag in evidence was not the bag he saw Oswald carry. Frazier claimed Oswald had the kind of bag one gets from a convenience store, made of thinner paper and not held together by tape. He also claimed Oswald’s bag was much shorter than the bag in evidence.

As it turns out, the bag Frazier and his sister Linnie Mae Randle claimed Oswald brought to work would not have been long enough to carry the disassembled rifle anyway. In the next article in this series, I will demonstrate why their claims about Oswald bringing a package to work that morning cannot be true at all. But even if Frazier’s story is believed, the bag in evidence could not be the one Oswald brought to work. In addition, no one ever witnessed Oswald bring the bulky, constructed bag with him to Ruth Paine’s home either—which he would have to have done if he had brought the rifle and bag with him to work from Mrs. Paine’s home the morning of the assassination.

The chain of evidence for the bag is broken, like so much of the evidence in the Kennedy Assassination case. The accounts given of its finding are conflicted and contradictory, as with so much of the evidence introduced in this case. No witnesses place the bag in Oswald’s hands at any time. The chain of evidence on the rifle palm print is also broken, and the explanation for its origin is even flimsier than the explanations given regarding the bag’s origin. In addition, paraffin casts taken of Oswald’s cheek by the DPD also showed no traces barium or antimony residue—which would have been there if he had fired a rifle that day.

Numerous witnesses saw a gunman in a TSBD window, and none of these witnesses identify Oswald as the man they saw—except one. Howard Brennan, the only witness who identified Oswald, did not do so when he saw Oswald at a police lineup. He only claimed to identify Oswald weeks later, then recanted his identification, then endorsed it again. Furthermore, this witness identified the man he saw as wearing different clothing than Oswald was wearing—and his description of this clothing matches the descriptions given by the witnesses who did not identify Oswald.

The documents purporting to show that Oswald ordered the rifle do not actually do so. Instead, these documents constitute evidence of a series of fabrications used to frame Oswald—as does the card bearing Oswald’s palm print. The only remaining evidence against Oswald are the fingerprints found on the boxes and the bag.

Fingerprint Evidence and Expert Foreclosure

Under regular circumstances, fingerprint evidence can counted on as reliable. In the case against Oswald, however, a pattern of law enforcement bias has been clearly established—including several instances of broken chains of evidence and the use of fraudulent documentation to link Oswald to the Mannlicher Carcano. As a result, the fingerprint evidence is clouded by questions of expert foreclosure.

A layperson cannot adequately judge expert interpretations of fingerprint evidence by checking the expert’s work—but other factors may constitute valid grounds for skepticism. These factors might include evidence of motivated bias on the part of the investigating body (including concerns about whether the fingerprints were planted), contrary determinations by other experts, or information casting doubt on the expert’s methods that can be explained and demonstrated to a layperson.

By way of example, I have already presented concretely corroborated proof of FBI corruption in fabricating the paper trail linking Oswald to the Mannlicher Carcano. In the FBI’s presentation of that false evidence against Oswald, handwriting experts were consulted to confirm that the writing on the photos of the rifle order form and envelope must have been created by Oswald’s hand.

Yet the FBI’s evidence for the rifle order merely confirms that Oswald was framed with false documentation—and that the FBI abetted and promoted (or created) that false documentation. This constitutes solid evidence of bias and corruption on the part of the investigators. As such, there is every reason to suspect their handwriting experts would have followed suit.

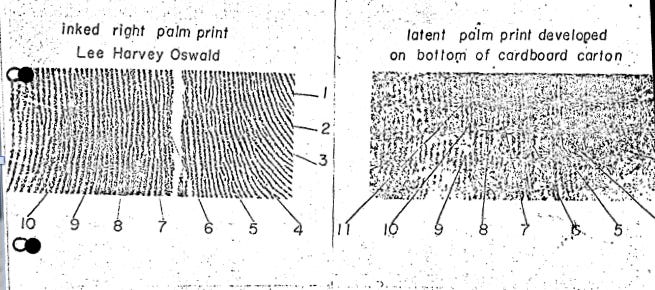

The same doubts can be raised regarding the FBI’s fingerprint experts who identified two of Oswald’s prints on the paper bag claimed to contain the rifle—especially since evidence already exists supporting fraudulence in the case of the rifle palm print. But even if the remaining prints attributed to Oswald were not planted, they could still be subject to misidentification by biased investigators—as with handwriting analysis. The DPD found no fingerprints on the bag, and initially, neither did the FBI. The prints were only identified by the FBI through application of silver nitrate, which is not a recommended method for porous surfaces like cardboard or paper.

In chapter 4d of Pat Speer’s online book, A New Perspective on the John F. Kennedy Assassination, Speer lays out an excellent case for rethinking reflexive trust in the practice of expert fingerprint identification. In recent decades, tests conducted on American fingerprint examiners found misidentification rates as high as 22%. Although fingerprint identification almost certainly has a greater scientific basis than handwriting analysis, subjective determinations are an inevitable component of the process.

As Speer goes on to explain, different standards exist among fingerprint examiners regarding how many points of similarity are required to confirm a fingerprint match. For most American experts, 12 points of similarity are required. In Europe, this number rises to 16. In contrast, the FBI of 1963 did not constrain themselves to any standard at all. Of the six prints offered as evidence of Oswald’s guilt, the number of points of similarity were 15, 13, 11, 11, 10, and 9. Only the first two prints on this list would have been considered an identification of Oswald by the American standard, and none of them would have been considered a match to Oswald’s prints by experts using the European standard.

The palm print claimed to be lifted from the rifle had 11 points of similarity, the fingerprint on the bag had 9, and the palm print on the bag had 15. The other three prints (13, 11, and 10) were found on the 6th floor boxes. As explained earlier, since Oswald handled boxes on the 6th floor as part of his regular job duties, these prints cannot constitute a case against Oswald. Pictured above is a comparison photo of Oswald’s palm print and the palm print found on the bag, as shown in the Warren Report. Let us take a look at a photocopy from FBI files of the palm print found on the bag, since it has 15 points of similarity—the highest number of any of the Oswald prints. The prints show up more clearly in this photo than in the one published in the Warren Report.

These prints don’t look anything alike to me. Of course, I’m just a layperson, not an expert. This exercise is a demonstration of the problems posed by expert foreclosure. A layperson can only accept an expert determination to the extent of the trust they confer on that expert. If the FBI had established a trustworthy track record in this case, I’d be willing to defer to their experts. But strong distrust has been established due to concretely corroborated fraudulence in the documents used to link Oswald to the rifle (for starters). Paired with the knowledge that none of these prints would be accepted as matching Oswald’s under the European standard, serious doubts are cast on the reliability of this fingerprint evidence.

That’s the last of the direct evidence pinning the shooting on Oswald. In short, there is none. At best, if a low standard of fingerprint identification is used, the evidence establishes that Oswald touched boxes stacked by the 6th floor window sometime in the three days before the shooting—and touched paper used by someone to create a bag found somewhere in the TSBD. Since Oswald handled boxes on the 6th floor as part of his job—and no evidence exists to show the bag was used to transport the rifle—this fingerprint evidence does not incriminate Oswald even if it is accepted as genuine.

Oswald’s Motive

In most murder investigations, suspects cease to be suspects when no direct evidence implicates them in the crime. But when it comes to Lee Harvey Oswald, this standard seems not to apply. A lot of people really wanted Oswald to be guilty (especially the investigators, who put forward clearly fraudulent evidence to tie him to the alleged murder weapon). Luckily for Oswald, he had no motive and a strong alibi. Or rather, it would have been lucky for Oswald—if he hadn’t been gunned down in a mob-style hit while in Dallas Police custody.

First of all, Oswald had no motive to kill Kennedy. Oswald’s proclaimed sympathy for Castro’s Cuba and the USSR would make President Kennedy a natural ally since Kennedy was actively promoting peace and rapprochement with these nations by 1963. Every witness close to Oswald was in agreement that Oswald liked and approved of Kennedy. That’s remarkable given the number of these witnesses who said other things to assist in throwing Oswald under the bus. One of the witnesses who proved most ruthless in her attempts to implicate Oswald was Ruth Paine. Within days of Oswald’s assassination she began advancing a narrative that Oswald must have wanted to kill Kennedy because it would transform him from a little person into “someone extraordinary.”

The first problem with this narrative is that Oswald already was someone extraordinary. At the age of 19, he made national headlines when he defected to the Soviet Union. By the time of his death at age 24, he had mastered the Russian language, completed a stint in the Marine Corps, lived for three years in the USSR, and had successfully returned to the United States. Kerry Thornley, who served with Oswald in the Marines, found him extraordinary enough to pen a novel based on Oswald entitled The Idle Warrior, completed in 1962—a year prior to Kennedy’s assassination. Other friends and acquaintances of Oswald’s included a future world leader, Stanislav Shushkevich (the first head of state of Belarus from 1991–1994), and George DeMohrenschildt, a dashing Russian-American aristocrat, oilman, and former (and perhaps not-so-former) spy, who was Oswald’s closest friend from late 1962-early 1963.

DeMohrenschildt himself was friends with future CIA Director and US President George HW Bush, and with First Lady Jackie Kennedy’s aunt, Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale (among other luminaries). As a child, Jackie Kennedy affectionately called him “Uncle Georgie.” Indeed, the evening after DeMohreschildt concluded his Warren Commission testimony regarding Oswald, Jackie Kennedy’s mother invited him to a dinner party at her home—also attended by her friend and neighbor Allen Dulles (Warren Commission member and CIA director from 1953–1961). Another of Oswald’s friends was Ruth Paine’s own husband, Michael Paine—scion of the illustrious Forbes family. Paine’s mother was married to Arthur Young, inventor of the Bell Helicopter, and her best friend was Mary Bancroft, onetime mistress and longtime confidant of the very same aforementioned Allen Dulles.

Those are some pretty extraordinary accomplishments for a 24-year-old, and a pretty extraordinary sampling of friends and acquaintances. Even as a child, little Lee Oswald brushed up against prestige. When his step-father Edwin Eckdahl filed for divorce from Oswald’s mother, he retained Fred Korth as his attorney. Korth became a member of the Suite 8F Group (kingmakers of Texas and US politics through oil, armaments, and financial leverage), and was later appointed US Secretary of the Navy by President Kennedy. He resigned in disgrace in October, 1963 due to corruption charges in conjunction with Vice President Johnson regarding a sweetheart deal with General Dynamics in Ft. Worth, Texas to build TFX fighter planes.

Oswald may or may not have considered himself extraordinary, but he did specifically reject any notoriety he might have gained as accused assassin of President Kennedy. Oswald repeatedly and emphatically denied the charges against him and famously shouted “I’m just a patsy” when paraded before the press by the Dallas Police. These are hardly the actions of an assassin seeking credit or attention through his actions. A compilation of Oswald’s statements to the press can be viewed here. Judge for yourself whether or not he seems sincere.

The Lone Gunman narrative requires ignoring the pertinent evidence in Kennedy’s assassination, which is an approach that makes little sense. It also requires a narrative about Oswald that makes little sense, and requires the belief that Oswald repeatedly acted in ways that make no sense at all. But regardless of how much or little sense these narratives make, concrete corroboration is able to help eliminate the possibility of Oswald being Kennedy’s assassin.

Oswald’s Alibi

President Kennedy’s schedule called for him to speak at the Dallas Trade Mart at 12:15pm by some reports and at 12:30pm by other reports. The motorcade would reach Dealey Plaza about 5 minutes before the Trade Mart (at 12:10pm or 12:25pm). The exact moment it would pass by the TSBD could not be predicted with accuracy. As it happened, the motorcade got off to a late start and reached Dealey Plaza at 12:30pm.

In order to ensure he wouldn’t miss his chance to kill Kennedy, Official-Narrative Oswald would need to quickly take position with his rifle at the beginning of his lunch hour. After all, he would still need to retrieve his rifle (that no one saw him carrying) from its hiding place and assemble it. The Warren Commission was forced to conclude he transported the rifle in a disassembled state in order for it to fit into the bag in evidence. They were also forced to conclude Oswald used a dime to assemble the gun since he had no tools available. This would take 6–8 minutes according to timed tests. If Oswald went down to the first floor for lunch, he would risk missing his chance to kill Kennedy and show the world he was a big shot.

But Oswald did go down to the first floor at the beginning of the lunch hour, as verified by multiple witnesses. He was also seen by Carolyn Arnold (either in the 2nd floor lunchroom or just inside the front door of the building, or both) sometime between 12:15–12:25pm. The remainder of Oswald’s alibi must be pieced together from notes taken during Oswald’s interrogations while in DPD custody. These statements by Oswald constitute concrete corroboration of his whereabouts on the lower floors just prior to the assassination.

TSBD workers Harold Norman and James “Junior” Jarman testified they went outside after eating lunch and waited on the sidewalk in front of the TSBD for Kennedy’s motorcade to arrive. After waiting for a few minutes, they decided they would rather watch the motorcade from the 5th floor of the building. Jarman specified that around 12:20–12:25pm, he and Norman walked around the back of the building to avoid the crowded front entryway and enter through the back door. They entered this door and proceeded up to the 5th floor, which they reached at about 12:25pm.

When Oswald was questioned by Dallas Police Captain Fritz and Federal agents, he stated that while he was eating lunch alone in the domino room he saw two coworkers walk by. FBI Agent James Bookhout’s summary of Oswald’s stated alibi reads as follows:

“OSWALD stated that on November 22, 1963, he had eaten lunch in the lunch room at the Texas School Book Depository, alone, but recalled possibly two Negro employees walking through the room during this period. He stated possibly one of these employees was called ‘Junior’ and the other was a short individual whose name he could not recall but whom he would be able to recognize.”

The domino room was located in the northeast corner of the TSBD, close to the back door entrance. Jarman and Norman were never asked if they entered the domino room before ascending to the 5th floor, but they would have been visible from the domino room even if they had only walked by. Norman and Jarman were both black, Jarman was nicknamed “Junior,” and Norman was quite short. Oswald accurately identified them as walking together in that area of the building, corroborating Jarman’s testimony. This account is verified in brief by Captain Fritz’s handwritten notes:

“say two negr. came in. One Jr. + short negro”

It is unclear whether Oswald claimed Jarman and Norman actually entered the domino room or whether he said they “came in” from the back door—we don’t have an actual tape recording or transcription of what he said. Secret Service Agent Thomas Kelley, who was also present, produced a report that varied markedly from the reports of Bookhout and Fritz:

“He said he ate his lunch with the colored boys who worked with him. He described one of them as ‘Junior’, a colored boy, and the other was a little short negro boy.”

The Warren Commission latched onto Kelley’s account and used it to discredit Oswald, ignoring Agent Bookhout’s report entirely. The Commission told Jarman that Oswald claimed to have eaten lunch with them. Jarman confirmed he did not eat lunch with Oswald, and the Commission moved on. But as Bookhout’s report shows, Oswald specified that he ate lunch alone and saw Jarman and Norman walking together. The testimonies of Jarman and Norman confirm that during the lunch hour, the only time they walked together alone in the vicinity of the domino room was during their journey from the street to the 5th floor.

It is not believable that Oswald would attempt to falsely claim having lunch with Jarman and Norman as Agent Kelley reported. It is believable, however, that Oswald would mention seeing those two coworkers in order to corroborate his presence in the domino room just before the assassination. After passing through the back door as they testified (which would have been about 12:22–12:23pm), their path to the staircase took them directly past the door to the domino room where Oswald observed them.

This information is very specific and is not a circumstance Oswald could have predicted or guessed. Oswald could not have provided this information had he not been where he said he was. Oswald’s report corroborates the reports of Carolyn Arnold, it is concretely corroborated by Norman and Jarman’s reports, and it is consistent with what Oswald said he did next: step over to the front door and have a look at the parade as it passed.

The DPD neglected to tape record any of their interviews with Oswald or have them transcribed by a stenographer. As such, reports about what he said are conflicting and sometimes suspiciously self-serving regarding key aspects of the DPD narrative. Agent Kelley’s version of Oswald’s report is a good example: one or two words of a suspect’s genuine testimony can be twisted or altered, changing the meaning and context entirely. A suspect’s alibi transforms into testimony that discredits the suspect or affirms the favored narrative of the prosecutors (or both).

This can be prevented when a suspect has an attorney present during questioning. Oswald publicly requested to have John Abt serve as his attorney. Abt was a lawyer well-known for representing communists whose civil rights were threatened by a biased legal system. If Abt could not be retained, Oswald’s second choice was a lawyer from the ACLU, an organization Oswald had recently joined. Although Abt did not step forward, the ACLU did approach the DPD with an offer of representation before Oswald was killed. The DPD told them Oswald did not want an attorney.

When a police force holds a suspect in custody for two days without providing him with an attorney, blocks him from meeting an attorney he did request, does not record their interviews with that suspect, and then that suspect is murdered in their presence—it is reasonable to doubt any self-incriminating or self-discrediting statements attributed to the suspect while in custody.

In contrast, any surviving reports of that suspect’s stated alibi in such circumstances are of crucial value. Oswald’s account of seeing Jarman and Norman, preserved by FBI Agent James Bookhout in his interrogation report, is supplemented by additional accounts of Oswald’s statements concerning his alibi. Dallas Police Captain Will Fritz was joined by FBI Agents James Hosty and James Bookhout for Oswald’s first interview in custody on November 22. Hosty’s original interview notes were only recently discovered by researcher Bart Kamp from fellow researcher Malcolm Blunt’s collection of National Archive documents. These notes were provided to the Assassination Records Review Board by Hosty in 1994. They corroborate the content of the report summary quoted above, which was prepared the following day.

The text reads: “O stated he was present for work at TBD on the morning of 11/22 and at noon went to lunch. He went to 2nd floor to get Coca Cola to eat with lunch and returned to 1st floor to eat lunch. Then went outside to watch P. (Presidential) Parade”

The final sentence about viewing the motorcade was omitted from Hosty and Bookhout’s official summary. But it is the key aspect of Oswald’s alibi. Its omission is further indication of efforts to obfuscate and suppress Oswald’s full alibi. Oswald claimed he went to the second floor to get a coke to go with his lunch—corroborating Carolyn Arnold’s report of seeing Oswald in the 2nd floor lunchroom at about 12:15pm. He claimed to have brought the coke down to the domino room where he proceeded to eat his lunch. While there, he observed Junior Jarman and Harold Norman walk by at about 12:22–12:23pm. When the motorcade finally arrived a few minutes later, he stepped up to the front door of the building to watch the parade when the motorcade finally arrived.

Prayer Man and the 2nd Floor Lunchroom

Oswald’s statement about going out to watch the parade is potentially corroborated by two films, dubbed the Darnell and Weigman films. They were both filmed by NBC cameramen from the motorcade and contain glimpses of the front steps of the TSBD. The Darnell film shows the TSBD moments after the shots were fired. In the image above, many believe Oswald can be seen at the top-left of these steps in the person of a blurry figure dubbed “Prayer Man” due to the distinctive position of his arms.

The frame shown below is from the Weigman film. It was filmed while the assassination was still underway, just prior the Darnell film. The same figure at the top-left of the steps can also be seen in this film, but is much harder to make out. The light shining at the point where his arms converge is thought to be Oswald’s bottle of coke, with the circular base of the bottle reflecting light as the bottle is tipped up to his lips for a drink:

Later photographs of the front steps show an empty bottle tucked in a nook just in front of Prayer Man’s location. On Bart Kamp’s Prayer Man website, a page dedicated to the bottle also displays a gif of frames from the Weigman film consistent with the figure in the photo above lifting his arm, tipping the bottle, and bringing bottle and arm down again. Shown below is the clearest photo from after the assassination of the bottle’s location in the nook beside the steps:

The identity of this figure may never be verified to universal satisfaction, though the original film copies (still held by NBC and never released to the public for examination) could provide higher resolution images. Either way, Oswald’s alibi does not depend on this evidence. But if Oswald did step outside to view the motorcade as it was arriving, it would make sense that he would be standing close to the door and behind the other spectators. The figure seen in these films, standing on the top-left of the steps, aligns with Oswald’s long-suppressed alibi. The figure also matches Oswald’s appearance closely enough for this to be a valid possibility.

Another reason these photos are thought to be Oswald is because researchers have exhaustively tracked down the location of every known TSBD employee at the time of the shooting. These employees are excluded from being Prayer Man either due to their known location, or because their known appearance does not match that of Prayer Man closely enough. Only Oswald remains as a candidate. This excellent Prayer Man summary on 22 November 1963 provides a breakdown of this accounting, and the prayer-man.com website provides a more extensive exploration of these questions, including copies of original document testimony for each witness.

These attempts to identify the location of each and every TSBD employee are naturally subject to dispute. Although Prayer Man’s position would be an odd spot to stand for a bystander not associated with the TSBD, it wouldn’t be impossible. No witness is on record claiming Oswald was the person standing there. On the other hand, no witness is on record identifying any person in this position.

Whoever Prayer Man is, it makes sense that he was not identified as present during the motorcade if he only stepped into position as the motorcade was arriving. The other witnesses would have been facing away from him, unaware of his brief presence. This would make little sense, however, if a stranger reached that position after climbing up the steps from the street. In any case, after the shooting stopped the Prayer Man figure would be seen by anyone who immediately turned around to enter the building or view the entryway.

As it turns out, there were some reports of Oswald being seen near the doorway immediately after the assassination. TSBD Vice President Ochus Campbell was standing in front of the TSBD steps at the time of the shooting. He was quoted as follows by the New York Herald Tribune in an article published on November 23: “Shortly after the shooting we raced back into the building. We had been outside watching the parade. We saw him (Oswald) in a small storage room on the ground floor.” Of the two 1st floor storage rooms in the TSBD, one of these is located in a stairwell directly adjacent to the entryway. (These front stairs reach only to the second floor and no further.)

The Dallas Morning News also published a relevant article on the 23rd, and also reported on Oswald’s presence in a storage room on the first floor—echoing the report of Ochus Campbell’s sighting. In this article, Campbell specifies that he was standing in front of the building with TSBD superintendent Roy Truly and observed Truly and a policeman rush into the building immediately after the shooting. The article goes on to report that this policeman encountered Oswald in the storage room as he ran into the building. Roy Truly stepped in to vouch for Oswald as a TSBD employee. Truly and the officer then continued on into the building.

At least four additional newspaper articles from November 23–26 referenced this encounter, described as happening either as the officer rushed into the building, as Oswald was leaving, or both. In each case, this indicates an encounter near the front entryway, as do the reports referencing the storage room. Deeper coverage of these reports can be read in Bart Kamp’s article, Anatomy of the Second Floor Lunchroom Encounter and in this summary of Oswald’s alibi from 22 November 1963.

The officer who rushed into the building and met up with Roy Truly turned out to be Marion Baker. Here is a copy of Baker’s November 22 affidavit:

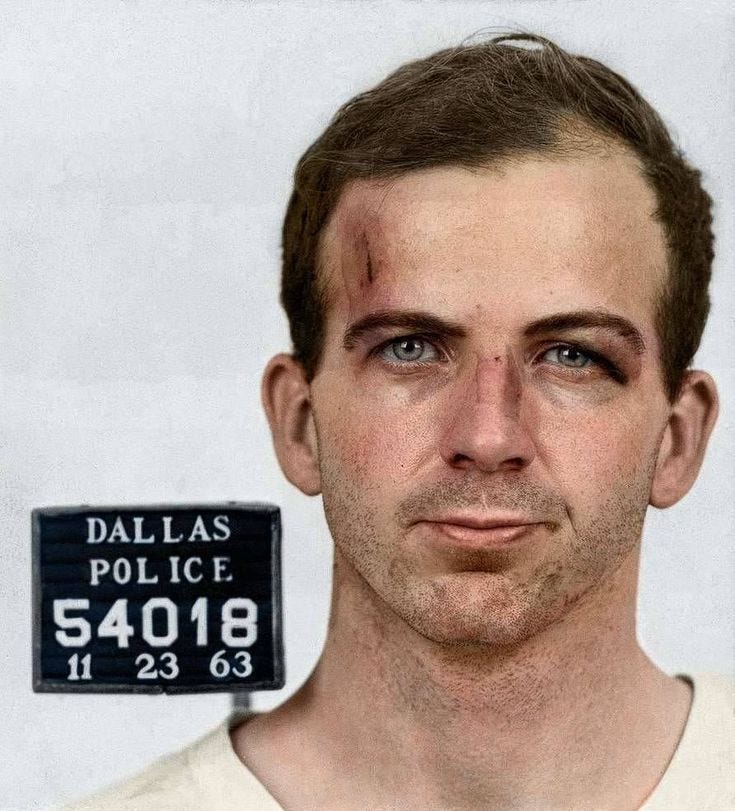

He describes encountering people at the front of the building and asking them for directions to the stairs to the roof. Truly steps forward and volunteers to accompany Baker and they proceed up the back stairs. Baker’s questioning of a man Truly vouches for as an employee does not occur until they reach the third or fourth floor. The man encountered does not fit Oswald’s description. Although he is judged to be 5’9”, which is Oswald’s height, and although Oswald was 24 years old but could reasonably pass for 30, this man is described as 165 pounds. At the time of his death, Oswald’s weight was measured as 131 pounds—remarkably sleight for a 5’9” man and unlikely to be mistaken for 165. The man Baker encountered was also wearing a light brown jacket, while Oswald was wearing a reddish shirt and no jacket.

A statement from Baker’s testimony to the Warren Commission contains an implication even more significant than these discrepancies. In it, Baker confirms he was present with Oswald in the same room of the DPD homicide office while submitting the affidavit shown above. If the man Baker had seen on the 3rd or 4th floor was Oswald, it is reasonable to expect that Baker would identify this man as Oswald in the affidavit, having seen Oswald at the very moment the affidavit was composed. He did not.

Meanwhile, Roy Truly submitted a statement of his own to the FBI that evening. In it, Truly claims he met Baker outside the TSBD and then rushed in with him to the first floor, where they saw no one. This contradicts Baker’s statement about rushing through the front door alone, speaking to several people who were there—and Truly stepping forward after this, offering to guide him. Truly also contradicts Baker’s report of spotting a man walking away from the staircase on the 3rd or 4th floor. Instead, he claims Baker “noticed a door and stepped through the door” after reaching the 2nd floor. On the other side of the door was Oswald in the second floor lunch room. Then, the familiar sequence of Truly vouching for the employee progresses and Baker and Truly proceed on up the stairs.

As time went by, Truly’s version of the account became the official narrative of the incident. When Baker later changed his account to align with Truly’s, he claimed to have seen Oswald through the window of the door and decided to rush in and confront him. The man walking away from the stairs on the 3rd or 4th floor, wearing a light brown coat (and not identified as Oswald by Baker), was transformed into Oswald already in the second floor lunchroom—not walking away from the staircase.

On its face, Truly’s statement about the 2nd floor encounter makes less sense than Baker’s account. According to Baker’s later reports, he thought the shots came from the roof of the TSBD because he saw a flock of pigeons fly away from the roof when the shots occurred. His stated purpose for entering the building was to reach the roof, which is where he and Truly went. A man on a higher floor walking away from the staircase leading to the upper levels would arouse more suspicion than a man seen through the window of a door on a lower level. A 3rd or 4th floor stairway encounter would also not require Baker to divert course from the staircase and enter a side room.

Press reports of an Oswald sighting just inside the front door of the TSBD disappeared as the official narrative converged on the second floor lunchroom encounter. A version of it persisted, however, in the Warren Commission testimony of US Postal Inspector Harry Holmes, who was present at one of Oswald’s DPD interrogation sessions. Holmes claimed that Oswald himself reported an encounter with a police officer at the front door. The officer began asking questions of Oswald and Truly stepped forward, telling the officer Oswald was an employee.

Curiously, in an interview with author Gary Savage years later, Baker also described encountering Oswald at the first floor front entryway, not on an upper floor. In this account, which appears in Savage’s 1993 book, First Day Evidence, Truly vouches for Oswald as usual. This raises the question of whether Baker’s initial account of encountering a man on the 3rd or 4th floor was fabricated from the start. Oswald was already arrested by that point and Truly and Baker may both have been pressured to relocate the encounter to the back stairwell. If so, Baker moved it to the 3rd or 4th floor, dropping all mention of Oswald—and Truly shifted it to the 2nd floor lunchroom, bringing Oswald there with him.

It is not possible to determine what really happened with certainty—but these conflicting accounts suggest that elements from separate incidents may have been patched together to craft a concocted narrative about Oswald’s movements. For instance, Oswald claimed to have gone to the second floor to get a coke before lunch, to drink with his lunch (as confirmed by Carolyn Arnold). If Oswald is the figure seen drinking from a bottle in the Weigman film, he presumably still had this very bottle of coke with at the front entryway during the motorcade and leaving it there after (potentially corroborated further by the Weigman film). After Oswald was murdered, The DPD and FBI changed their reports, now claiming that Oswald confirmed going to the 2nd floor lunchroom for a coke after the assassination—where Baker and Truly encountered him.

The post-assassination 2nd floor coke story was further promoted through the testimony of TSBD employee Geraldine Reid, who was standing in front of the building with Roy Truly and Ochus Campbell at the time of the shots. In her November 23 statement, she claimed she returned to the building, proceeded alone to the 2nd floor office where she worked, and arrived about 2 minutes after the shots were fired. This office is adjacent to the 2nd floor lunchroom. There, she claims to have seen a TSBD employee passing through the office from the lunchroom. She recognized him but did not know his name, and she claimed he was carrying a coke and wearing a white tee shirt. After Oswald’s arrest, she confirmed that the man she saw was Lee Harvey Oswald.

Reid’s testimony is contradicted by Geneva Hines, who was present in that office during and after the shooting. Hines testified that she was alone in the office for about 5 minutes after the assassination and no one passed through it during that time—neither Oswald nor Reid. The first people to enter the office came in a group of four or five, and this group included Mrs. Reid. The testimony of Reid is also contradicted by the Truly-Baker narrative, which had Oswald wearing his reddish shirt at the time of their lunchroom encounter, not a white tee shirt.

Because of these two holes in Reid’s testimony, her story weakens rather than strengthens the narrative of the 2nd floor lunchroom encounter. Instead it adds more weight to the likelihood that witnesses like Reid, Truly, and Baker were pressured to align their reports with the emerging narrative—transposing Baker and Truly’s encounter with Oswald from the 1st floor entryway to the 2nd floor lunchroom. When Reid stood in front of the building, she was accompanied by Truly and Campbell—the very two TSBD personnel named in reports of Oswald’s front entryway encounter. Because Reid was with them, this raises questions about whether Reid had seen Oswald at the entryway along with Truly and Campbell. If so, this explains why she would have been pressured to submit a false account of a 2nd floor Oswald encounter.

The alternative explanation for all this is that the 2nd floor lunchroom encounter really did happen, and all of the conflicting reports are an artifact of mistake and confusion on the part of the witnesses and those who took their reports. For now, let us hold open both possibilities while noticing the established pattern of omitted and altered witness reports:

Carolyn Arnold was never called to testify by the Warren Commission. Oswald’s pre-lunch coke became a post-lunch coke. Encounters with Oswald in the building entryway became encounters in the 2nd floor lunchroom, as did Baker’s encounter with an unknown man on the 3rd or 4th floor. These alterations—along with the alteration of Oswald’s sighting of Jarman and Norman from the domino room and the omission of Oswald’s claim to have gone outside to view the parade—erased Oswald’s presence on the first floor before, during, and just after the assassination. The assassination of Oswald became the final erasure.

Ironically, the 2nd floor lunchroom encounter is pointed to by both Oswald-did-it proponents and Oswald-didn’t-do-it proponents as supporting their case—though the incident may have never occurred. For Oswald-as-Lone-Gunman advocates, this encounter is seen as consistent with Oswald’s recent departure from the 6th floor window where he shot the president. They argue that Baker and Truly would have arrived at the 2nd floor 75–90 seconds after the final shot. They believe this would have been enough time for Oswald to wipe his prints off the rifle, hide it, and hustle down the stairs—nonchalantly purchasing a coke from the second floor vending machine to explain his presence there.

The timing is subject to debate, but Oswald-is-Innocent proponents usually argue that 90 seconds was not enough time for all these actions to have occurred (let alone 75 seconds). They also point to the testimony of Vickie Adams, who ran down the stairs from the 4th floor with coworker Sandra Styles in the seconds following the final shots. Adams and Styles did not see or hear Oswald (or anyone else) on the stairs. Both elevators were hung up on the top levels at the time Truly and Baker reached the base of the stairwell, so if Oswald had descended from the 6th floor to the 2nd floor in time to encounter them, he can only have used the staircase.

The Warren Commission and other Lone Gunman proponents attempt to solve this issue by claiming Adams and Styles were wrong about descending the stairs immediately and did not do so until after Truly and Baker ascended. But Adams and Styles are concretely corroborated by their supervisor Dorothy Garner, who confirmed they left immediately. Garner followed them to the top of the stairs, arriving in sight of the stairwell a few seconds after they descended. She verified that Baker and Truly came up the staircase after Adams and Styles, and she did not see or hear anyone else come down the stairs.

The Stroud document (pictured above) confirms that Garner’s reports were available to the Warren Commission but were ignored. Like Carolyn Arnold, Garner was never called to testify. If the 2nd floor lunchroom encounter with Oswald actually occurred, he could not have descended to the 2nd floor by elevator or stairs following the shooting, could not have been on the 6th floor at the time of the shooting, and could not have been the shooter.

The 2nd floor lunchroom encounter may have been a fabrication cobbled together from several misconstrued elements: Oswald’s presence in the 1st floor lunchroom (domino room), Oswald buying a coke from the 2nd floor lunchroom vending machine, encounters with Oswald at the front entryway, encounters with Oswald holding a coke (if he is the figure in the Weigman film, Oswald could have been seen with a coke at the entryway), and Baker’s encounter with a different man on the 3rd floor (Garner’s account rules out the 4th floor). The need to incorporate and transform the coke and the lunchroom elements of Oswald’s alibi would explain the purpose in moving Baker’s 3rd floor encounter down to the 2nd floor vending machine in the lunchroom.

The Oswald-as-Lone-Gunman narrative would have held up better without the 2nd floor lunchroom incident, freeing up other proposals to explain Oswald’s departure from the 6th floor while eluding detection. Only the need to bury Oswald’s alibi and the evidence supporting it explains why the 2nd floor encounter would have been invented. Without it, every piece of evidence regarding his whereabouts at the time of the shooting points to his presence on the first floor.

Summary of the Evidence

As stated earlier, two primary beliefs seem to be at the core of the Lone Gunman interpretation of the case: that the evidence against Oswald is overwhelming, and the level of official corruption necessary to have framed Oswald and covered up for the true assassins is not believable. The evidence and fact pattern above shows that the evidence against Oswald is not overwhelming, it is entirely absent. Moreover, official corruption in presenting false documentation to link Oswald to the rifle is unassailable. Other instances of official corruption are also evident through numerous instances of broken chains of evidence, suppressed and altered reports of Oswald’s stated alibi, and suppression of witness testimony that supported his alibi.

Multiple witnesses who observed a man with a rifle in the TSBD window did not identify Oswald, and described the man’s clothing as different from what Oswald was wearing that day.

The only witness who identified Oswald as the man in the window did not do so when confronted with Oswald in a police lineup. He changed his testimony later and identified Oswald after the fact, then recanted his testimony, then later recanted his recantation. He described the man in the window as wearing clothing similar to that described by other witnesses—not the clothing Oswald was wearing that day.

Witnesses who did identify Oswald saw him on the lower floors. After he was seen on the first floor by multiple witnesses at the beginning of the lunch hour, he was never seen on the 6th floor, was never seen going to the 6th floor, and was never seen on a floor higher than the 2nd floor.

Concrete corroboration establishes that Oswald was present in the first floor domino room as late as 12:23pm.

The chain of evidence tying the Mannlicher Carcano to the 6th floor (or the TSBD in general) is broken. Initial documentation and reports from November 22–23 list a 7.65 Mauser as the rifle found.

The documentation linking Oswald to the Mannlicher Carcano is fraudulent. Not only does the evidence fail to show that Oswald ordered, paid for, and received the Carcano, the evidence shows he was framed for this using false documents procured and presented by the FBI.

The card bearing the palm print that linked Oswald to the Carcano has a broken chain of evidence. This card only materialized in evidence 5 days after Oswald had been assassinated.

Oswald was assassinated while in Dallas Police custody.

He was assassinated by Jack Ruby, a man with extensive ties to both organized crime and the Dallas Police.

Oswald was blocked from obtaining a lawyer while in custody.

The bag supposedly used by Oswald to carry the rifle to work has a broken chain of evidence.

Lab analysis of this bag showed no marks or stains on it consistent with it ever holding a rifle.

No witness ever saw Oswald carrying this bag at any time.

The only witnesses who claimed to have seen Oswald carrying a package to work that day insisted the bag in evidence was not the bag they saw. They furthermore insisted the bag he was carrying was too short to have carried the Carcano, even when disassembled.

None of Oswald’s interrogations were transcribed by a stenographer or recorded. Oswald’s statements regarding his alibi were misconstrued, altered, and used against him by the DPD and FBI, or else suppressed entirely.

Carolyn Arnold’s testimony backing up Oswald’s alibi was ignored. She was never called to testify before the Warren Commission.

Dorothy Garner’s proffered testimony regarding movement on the back staircase was ignored. Her account established that Oswald could not have been on the 6th floor if he was encountered by Baker and Truly on the 2nd floor lunchroom. She was never called to testify before the Warren Commission.

Paraffin tests of Oswald’s cheek showed no residue, indicating he had not fired a rifle that day.

Unless belief in Oswald’s guilt is assumed through narrative frontloading, there is no reason to believe or even suspect Oswald fired any shots at Kennedy. None of the evidence shows that. None of the evidence even points to it. The reports of street witnesses suggest the gunman was a white man wearing light-colored clothing with an open-neck shirt. As far as I can determine, Jack Dougherty was the only white male TSBD employee who may have been located on the upper floors at the time. No reports indicate the color of his clothing that day. More likely, the gunman was not an employee at all. If so, he would either have gained access to the building with the assistance of an inside collaborator, or by sneaking in alone and holing up in a hiding place until the noon hour.

Several street witnesses who saw a second man standing near the gunman described this man as wearing a brown suit coat. A man in a brown suit coat was also observed by two street witnesses running out the back door of the TSBD and then being driven away in a getaway car. This brings to mind Marion Baker’s initial reports of stopping a man in a light brown jacket on the 3rd floor. If law enforcement had been interested in finding the actual killer, this lead would have been investigated along with the others listed above.

The DPD and FBI never showed any serious interest in following leads in the case. All efforts were expended toward one end only: making a case against Lee Harvey Oswald—even if fraudulent and faulty evidence was required to do so. The Dallas Police and Henry Wade (Dallas County district attorney from 1951–1987) had an established record of railroading suspects to obtain false convictions. With 19 convictions overturned by DNA evidence (15 of these from Wade’s tenure), and over 250 more that are still under review, no county in the United States has been found to convict more innocent people than Dallas. Errol Morris’s 1988 film the Thin Blue Line, documents the wrongful murder conviction of Randall Dale Adams by Dallas Police in 1978—featuring none other than detective Gus Rose (who worked on the Oswald case and is credited with discovering the backyard photos) as instrumental in framing Adams.

The Oswald Impersonations

The final set of evidence I will present to establish Oswald’s innocence in the assassination of Kennedy consists of concrete corroboration that in the months leading up to the assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald was repeatedly impersonated, and a number of these impersonations can clearly be seen as attempts to plant witness evidence implicating Oswald as the patsy in the Kennedy Assassination before the fact.

The most important of these impersonations occurred in Mexico City. Beginning on September 25, 1963, a trail of confused and conflicted evidence and witness testimony begins. This evidence and testimony weaves a narrative in which Lee Harvey Oswald departs New Orleans by bus on the 25th, crosses into Mexico on the 26th, and spends the next week in Mexico City. There, he makes a series of visits and phone calls to the Cuban Consulate and Soviet Embassy, attempting to receive a visa to travel to Cuba. At the Soviet Embassy, he speaks with Valeriy Kostikov, rumored by the CIA to be a KGB agent with responsibility for conducting assassinations. Uncorroborated testimony later surfaced implicating Oswald as accepting $7,000 cash payment from a red-haired black man while in Mexico. Oswald was alleged to have made reference to killing someone as he accepted the money.

No concrete evidence has emerged to establish truth in the maze of strange stories that comprise the Mexico City episode. One of the most consistent recurring elements in the Mexico City stories is that the man identified as Oswald was not actually Oswald. He was described in an array of different ways, with physical characteristics diverging wildly from Oswald’s actual height, weight, hair color, and build. The man was described as speaking Spanish (Oswald did not speak Spanish) and very poor, broken Russian (Oswald spoke excellent Russian).

Immediately after the assassination, FBI agents reported to J. Edgar Hoover that surveillance audio and images of Oswald in Mexico City (provided by the CIA) showed the man did not have the voice or appearance of Oswald. Later, the CIA claimed these audio recordings never existed—assuming Hoover’s FBI agents were not fabricating their internal reports about having heard these recordings, it seems the CIA must have destroyed the recordings and lied about the recordings having never existed. It is also unclear what images the CIA presented to the FBI. It might have been the image shown above (at far left), an image of a man who is clearly not Oswald.

Photographs of this man are all that remains of CIA surveillance imagery in Mexico City concerning Oswald. The center and far right images shown above were provided by the Cuban government from their own surveillance photos in Mexico City. Cuban officials claim to have no surveillance images that match the appearance of Lee Harvey Oswald, but believed one of the two men pictured above may have been the man claiming to be Oswald in Mexico City.

The reason this Mexico City trip is important is twofold. On the day of Kennedy’s assassination, CIA and FBI reports about Oswald’s supposed trip—especially regarding his efforts to connect with Cuba and the Soviet Union—were used to warn the White House and Pentagon that Oswald may have been an agent of a Soviet or Cuban plot to kill Kennedy. The Johnson Administration risked the prospect of international tensions escalating if Oswald was determined to have conspirators in a plot to kill Kennedy. In light of Oswald’s known history of defecting to the Soviet Union and living there for three years, his Mexico City contacts with agents of Cuba and the Soviet Union could generate demands for a US military response—including the possibility of initiating World War III as the consequence.

Moreover, many voices of influence in the Pentagon and National Security apparatus welcomed the chance for war and hoped to fight it, win it, conquer Castro, and defeat the Soviets—regardless of whether nuclear warheads were used along the way. The alternative to risking this outcome was to make the case that Lee Harvey Oswald killed Kennedy and acted alone. This second option was the one selected.

The second reason the Mexico City trip is important is because the evidence shows the man claiming to be Oswald in Mexico City was not the same man later accused of killing the President. This means Oswald was impersonated—which means he had already been selected as the fall guy in Kennedy’s planned assassination. Due to the CIA’s role in fanning the flames of disinformation and paranoia around the Mexico City event, this raises suspicions that agents within the CIA were involved in setting up the event, and therefore in the assassination of Kennedy.