JFK and the Doorways to Perception, Part One

Unlocking the doors to the Kennedy Assassination

Any person who examines the Kennedy Assassination achieves entry into the case through one or more initial doorways. Beyond those doorways exists a portal with the power to change our perceptions about the world we live in—to bring relationships and dynamics of power, cause, and consequence into deeper levels of understanding and wisdom in our minds and hearts.

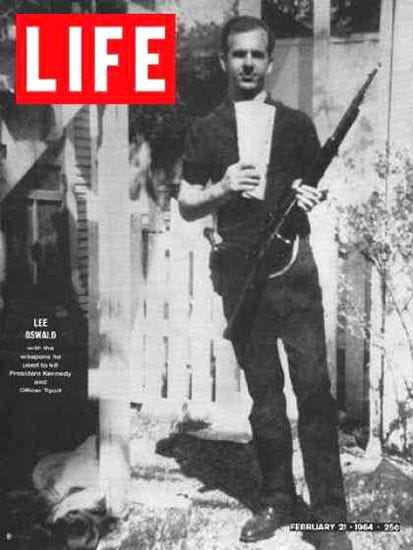

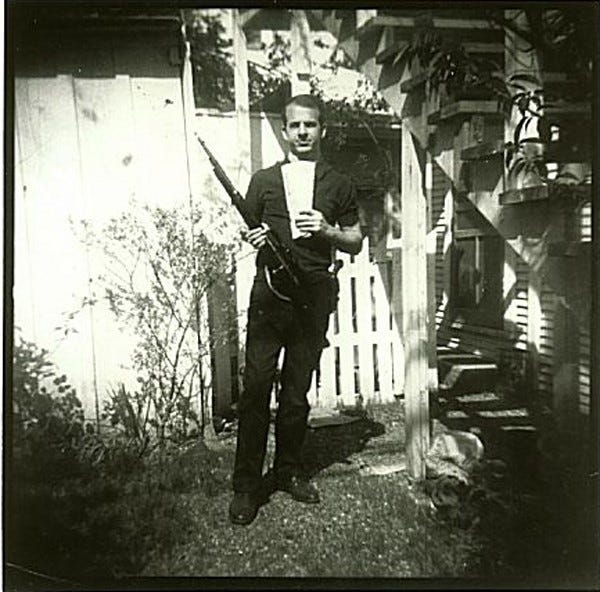

Whether you are encountering the study and lore of the JFK Assassination for the first time, or you are wondering how to introduce others to the case, it is useful to visit (or revisit) those initial doorways of entry. I have identified three image sets that capture the story of my own entry into this historical event: A photograph of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald (pictured above), the “backyard photographs” of Oswald brandishing two guns and two communist newspapers, and the 8 millimeter Zapruder film that captures the shooting of John Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963.

William Blake once wrote of the Doors of Perception, capable of unveiling the eyes to a true vision of the world and cosmos. In a smaller, more specific way, the three image sets referenced above serve as doorways to perception. They are themselves images—objects of perception—subject to differing meanings and interpretations by the bearer of the eyes that behold them. With the benefit of a little context, these images hold transformative potential in the perceiving power of the viewer. New worlds of possibility and recognition become accessible to the mind. These doorways carry us through corridors of knowledge to a portal that expands our perception—though the world remains unchanged.

In sharing my own process of engagement with the case, I will explore the paths that lead to these doorways, the locks that keep them closed, and the keys that unlock them.

My introduction to the case came at Pizza Hut. My parents periodically took my sister and me there for dinner when we were kids. Somehow, more than anywhere else, the environment at this particular chain restaurant led them to teach us about history while we ate. This is where my love for history began. To me, history is the greatest story ever told. In fact, every story that has ever been told is simply a smaller story within the one great, all-encompassing story of history. The best historical stories are the ones that are actually true. Winnowing fact from fiction in the great narrative of history is challenging but rewarding. The closer one gets to truth in history, the more alive it becomes—the more wondrous, the more captivating.

When I was eight, my parents told me the story of how 25 years ago, President John Kennedy was shot and killed while riding in a motorcade through Dallas, Texas. They told me how the police picked someone up as a suspect soon afterwards—and how within days another guy shot and killed the suspected assassin under police escort on live TV. They told me how crazy it all seemed at the time—like the whole world was going nuts. They told me about the Cold War, the civil rights movement and the end of racial segregation, about the Vietnam War, the protests, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy that followed. They told me how quickly society changed in those years—how exciting and frightening it all was. And they told me that some people believed there were conspiracies behind these murders, but that probably all of these murders were done by lone assassins. They explained that the ‘60s were a crazy time and a lot of people were acting in crazy ways because things were changing so fast.

I was enthralled by the story of the ‘60s. My father also told me about the Cuban Missile Crisis: how with Kennedy as president, we came to the brink of global nuclear war—how nobody knew if the world would survive—and how Kennedy and Soviet Premier Khruschev came to terms and stepped back from the brink. My father was in officer training school in the Navy at the time. He and the other members of his cohort were sequestered at their training facility with no news for days about how the crisis was unfolding. He told me how the following year he was aboard a naval ship in the Pacific Ocean when news of Kennedy’s assassination broke—how his ship immediately changed course, now heading west toward Russia in case it turned out the Soviets were responsible for Kennedy’s death and our countries would go to war.

I was casually interested in the idea that there could have been more to Kennedy’s assassination than a lone gunman, and thought it seemed suspicious that the suspect in the case was assassinated just days after Kennedy—by another lone gunman. But I accepted my parents’ assertion that there was probably nothing more to it than the wildness of the times. It seemed tragic that three great leaders were killed by deranged but ordinary citizens in a time of high idealism. My parents mentioned that if these leaders had lived, history might have gone very differently—likely for the better. But ultimately, it was comforting to know that things were not that complicated. Tragedy could occur, but it was part of life. The country was strong enough to handle it and carry on.

I later learned that Kennedy’s accused assassin was named Lee Harvey Oswald, and his assassin was named Jack Ruby. This is the first doorway into the case; that’s why I featured the image of Oswald’s murder at the top of this article. Without context, the image of Ruby shooting Oswald is simply an iconic moment of chaos in a chaotic time. It was disappointing that the president’s assassin was killed before he could stand trial and possibly reveal why he did it, providing clarity and closure, but it also seemed fitting. Oswald had lived by the gun and died by the gun. Suspicious on its face, perhaps, but without further information, it’s possible to write it off as “just one of those things.”

But what if others had assisted Oswald in his crime? If so, the image carries a different emotional register and importance. The murder of Oswald silenced him. Those who assisted Oswald in killing Kennedy got away with it. Who might those people have been? The likelihood that Ruby was one of those conspirators would seem increasingly probable. The image becomes more sinister. Questions start to arise—how did Ruby get that shot off while surrounded by police? Did they help him do it? They’re all just standing there, letting it happen. What was really going on here?

And what if Oswald hadn’t killed Kennedy at all? Now the image becomes even more sinister, as well as deeply tragic. Here is Oswald, a human sacrifice: a scapegoat in the most precise sense of the term. What was he feeling when he was shot? Surrounded by predators, the whole world turned against him, transforming him into their fall guy. Oswald became the poison container for the crimes of a bloodthirsty, vengeful, cynical society—his face contorted in the pain of mortal injury—and of betrayal. The image becomes haunting: a condemnatory artifact of a corrupt nation, vibrant with sorrow and heartbreak. If we don’t know whether Oswald killed Kennedy—if he did so alone or with conspirators, or if he didn’t do it at all—the image contains all of these conflicting possibilities, meanings, and emotions at once.

I never saw this image of Ruby shooting Oswald until years later, but the story of Oswald’s murder was the first doorway to the case I encountered. When I was 11 years old, I remember hearing about the film JFK and the controversy surrounding the movie. My parents had previously assured me that the conspiracy theories about the assassination were mostly conjecture and fantasy, but now the whole country seemed to be questioning that fact. It made me think there might be something to those theories after all.

I even remember the night when my parents went out together to see the film in theaters. I would have liked to watch it with them, but they didn’t invite me to join. I wish they had—my parents saw fit to take me to see Silence of the Lambs in theaters earlier that year. I found Silence of the Lambs horrifying and disturbing at that tender age, and I’m sure I would have been better served by seeing JFK instead. I find it interesting they chose to shield me from seeing JFK, but exposed me to images of Hannibal Lecter eating peoples’ faces off. Somehow questioning our government and the established narrative of official history was seen as a riskier exposure for an 11-year old than a movie about a serial killer who kidnaps women and keeps them imprisoned in a hole in the ground before eating them and wearing their skin.

I asked my parents what they thought of JFK when they came home from the theater the night they saw it. They were dismissive. They agreed the movie was well done and entertaining, but didn’t believe it was telling the truth. They didn’t explain to me why they thought that, and I never found out. They just kind of indicated that it was probably embellished and loose with the true facts because it would be a more exciting movie that way.

I was a little disappointed, and my interest in the case died down again. I trusted my parents’ judgment, and figured if they weren’t convinced by the conspiracy theories, I shouldn’t be either. But sometime in the next few years, I happened across a TV exposé about the Kennedy assassination, which introduced me to the second doorway into the case: the image displayed below.

There he was, the man himself, on the cover of Life Magazine: Lee Harvey Oswald, wicked assassin of President Kennedy, arrogantly posing with his rifle, his handgun, and his communist newspapers—just like a villain from the old Batman reruns I used to watch on TV at the time. Oswald wanted to show off. He wanted everyone to see how evil he was; he was proud of his criminality. In fact, he even looked crooked, just like those Batman villains. Whenever the camera visited the criminal hideouts of the Batman villains, the camera was tilted crooked. Everything was diagonal—nothing on the level.

Oswald apparently didn’t care if he was caught since he had these incriminating photos taken of him. He probably wanted to get caught so everyone would know he’s the one who did it. That’s what the Batman villains would do too: each episode they would explain every detail of their planned crimes right before attempting to complete the crimes. This would always lead to them getting caught, but the villains never learned. Just like Lee Harvey Oswald, Batman villains cared more about being recognized for their criminal cunning than eluding capture.

The image of Oswald on that magazine cover looked so creepy to me. It looked like a snapshot of evil, an encapsulation of everything wrong with the world. It gave me a weird feeling. But a little later in the program, the narrator explained that many critics believed the photo was fake. And then he demonstrated something that has stuck with me ever since: Both of Oswald’s heels are outside his center of gravity. I’ve marked this with a straight line on the image of the full photograph below.

Oswald’s navel is directly above the outside edge of his right foot. His left hip is directly above the inside of his left foot. His left shoulder is centered above the gap between his feet. His upper torso is straight upright while is legs both stretch diagonally at a slant to his left side. It is impossible to stand in this position unless you are leaning against a wall or your left shoe is cemented into the ground. Go ahead and try. Stand in front of a full length mirror and try to duplicate this pose without falling over. It cannot be done; it is an impossible stance. I don’t know how many times I’ve tried over the years. I’ve never even come close.

With this observation, the comparison to the skewed camera angles when depicting the villains on the Batman TV show seems even more appropriate—but in this case, it’s Oswald’s body that is skewed and impossibly diagonal. It makes one wonder if the creators of Batman drew inspiration from this photo when the show first came out two years after this issue of Life magazine.

The unnatural and impossible lean in this image is even more starkly apparent when the image is reversed, as displayed below:

Unless it were somehow possible for Oswald (or anyone) to stand in this position, the impossible pose could only be accomplished by superimposing the image of the body over a photograph of the empty backyard. Two other backyard photos exist in which Oswald’s body is standing straight, but when the “impossible lean” photo was created, it appears a mistake was made and the image of the body was placed on it crooked. The originating photo is itself already slightly titled, as can be seen by the fact that the slats of the fence and paneling on the structure behind him and to his left skew slightly to the right on the photo, rather than going straight up. This tilt makes his lean appear slightly less pronounced, but still impossible.

On the cover of Life Magazine, the photo’s tilt has been corrected (the fence and wood paneling point straight up), showing Oswald’s lean to be even more impossible than it it looks in the original slightly tilted photograph. It’s almost as if Life magazine was shoving the impossible photograph in the public’s face to prove they can force them to believe anything through the power of authority. Or maybe they preferred to make the Wizard of Oswald look even scarier by demonstrating his power to defy gravity.

For another point of comparison, I created a strongly tilted version of the photo, posted below, which shows how skewed the background has to be for the body to be aligned upright:

On its own, Oswald’s impoosible lean is enough to convince me the photo was faked. Any argument in favor of this photo’s authenticity must demonstrate how Oswald’s lean is physically possible. Attempts to demonstrate this through virtually constructed digital computer models have been made, but no attempts to demonstrate this in the material world with physical bodies has been successful. Numerous other aspects of this photo and the other backyard photos make the case for forgery a slam dunk certainty, which I will address later.

When I first saw the cover of Life Magazine featuring this image of Oswald, I felt an eerie feeling. At the time, I had no thoughts about the photo being fake—I just thought I was creeped out by an image of Kennedy’s cold-blooded assassin. Later, when the impossibility of the photo was demonstrated to me, that eerie feeling was transformed: An eerie feeling is a signal from the subconscious mind to the human emotional system that something is out of place. Some aspect of truth and reality is missing or unseen. The skewed image available to the mind and eye is a distorted picture, and the distortions point to the source of what is hidden.

Applied to the “Oswald lean” photo, the eeriness of the image points to the unseen forces that brought about John F. Kennedy’s death and removal from power. In its superficial representation of Oswald as the lone wolf killer, the unseen energies are the psychological disturbances that motivated his crime. When attention turns to the diagonal stance of Oswald’s legs, the mind recognizes this impossible position as the previously unseen influence on the image—seen but not seen. Hidden in plain sight. It begs the question of what else lies hidden in plain sight in the story of Oswald and Kennedy.

If the image of Oswald was manufactured, who was responsible for doing so? And who was responsible for promulgation of the image? Viewed this way, it portrays more than a haunting image of a man with evil intentions—it now displays evidence of multiple people involved in framing this man for the murder of the president, aiding and abetting the people actually responsible for the crime. The emblem of Life magazine endorsing and the photo becomes significant. The eeriness of the image still points to the unseen forces behind the Kennedy assassination—but it points to the creators and promulgators of the photo, not to the subject of the photo.

All of this was lost on me when I was a teenager. While I never forgot what I saw on that TV program about the assassination, it did not convince me that Kennedy was the victim of a conspiracy. In some ways, that level of skepticism on my part was healthy. I knew better than to believe everything I saw on TV, and I knew there was a lot about the world that I didn’t understand. I filed away the evidence about the photograph for future consideration. I presumed that someone somewhere would be able to explain why the photo wasn’t actually fake, how Oswald’s impossible stance was somehow possible, or how it was all some kind of optical illusion. Someday, someone would explain it to me and I would see through it like seeing through a magician’s trick.

Besides, even if the photo was faked, it didn’t necessarily mean Oswald was innocent of shooting Kennedy. Perhaps Oswald really did kill Kennedy and really did act alone, but the authorities were a little overzealous in trying to keep the public from imagining false conspiracies. Maybe they overplayed their hand by patching these photos together after the fact—even though this false evidence was unnecessary. After all, what difference did it make if this image of Oswald was taken somewhere else and pasted in this backyard setting? The image still portrayed Oswald holding his murder weapons and literature of criminal inspiration, and that was what was important.

I didn’t want to be the sucker who fell prey to a bunch of hucksters spinning wild tales and conspiracy theories. Besides, even if the image of Oswald holding these items turned out to be authentic, it didn’t prove he was the shooter of Kennedy. It’s lack of evidentiary value paradoxically implied the presence of hard evidence elsewhere. If the official institutions of our country insisted that Oswald killed Kennedy and acted alone, they must have the evidence to prove it. How could they all be wrong or lying in coordination with each other? This photo was superfluous evidence, whether faked or authentic. My parents saw Oliver Stone’s JFK and weren’t convinced by it. Probably if I saw the film myself, I would also identify all the reasons the conspiracy theories didn’t hold water.

A few years later, in my junior year of high school, I had an American History teacher who was interested in the Kennedy assassination; she devoted an entire week of the class to exploring the case with us. She clearly believed there was credible evidence for a conspiracy, though she implored us to make up our own minds after reviewing the evidence she exposed us to. But I was already a stubborn contrarian at the time. Any time I was confronted with teachers or authorities who strongly wanted me to believe something, I gravitated to the opposite position as a matter of principle. It was ironic that in the case of the Kennedy Assassination, I adhered to the lone gunman theory promulgated by the highest authorities—believing myself to be a rebel against authority because my high school teacher had presented us with the opposing view.

At the end of the Kennedy Assassination week, she had us all raise our hands to indicate which side of the coin we had landed on. I was one of the only kids in my class who raised my hand in support of the Oswald-as-lone-gunman conclusion. When asked to present my reasoning, I said something sarcastic and obstinate, sticking to my guns, but I didn’t really have good reasons to support my conclusion—and I knew it.

The truth was, I hadn’t paid much attention to her presentation of the case; I had already made up my contrarian mind at the beginning of the week. But when I was pressed to explain my reasoning, I knew in my heart that I couldn’t back up my position, and I secretly felt a little embarrassed. The memory of that stuck with me. For the next few years, I wondered if I ought to give the case an honest look someday and find out where the evidence would lead. I still remembered the program I had seen that demonstrated Oswald’s impossible stance. But I didn’t look into it.

Unlocking the Doorways and Narrative Frontloading

By now, I had encountered two doorways into the Kennedy assassination: evidence of forgery in the Oswald backyard photo, and Ruby’s assassination of Oswald. But even with the rare benefit of a week of high school classes prompting me to explore those doorways, those doors remained locked shut. The name of the lock that kept these doors closed is a concept I call narrative frontloading. At the time, I held a pre-existing narrative that told me the official institutions of government and establishment press corps would not both conceal the truth of John Kennedy’s assassination—and would have failed to do so if they tried. With narrative frontloading, certain beliefs are already fixed in place prior to the examination of evidence. Evidence or reasoning that contradicts this belief is discarded as soon as the contradiction is made apparent. The mind concludes, “There must be something wrong with this evidence or line of reasoning. Even though I can’t detect the evidentiary or reasoning flaw, I know it must be flawed because I know my pre-existing narrative is true.”

In an accurate reasoning process, narratives must fit the evidence. If a narrative does not fit the evidence, the narrative must be discarded, not the evidence. Narrative frontloading reverses the process and discards evidence that does not fit the narrative. It’s the primary basis of what I call narrative fallacies: reasoning mistakes that create or support a frontloaded narrative.

For me, the 2000 US Presidential election was the event that crashed through the foundations of my frontloaded narrative and unlocked the doorways to perception in the Kennedy assassination. At the time of the election, I was living in England on an undergraduate student exchange program. I watched the US election coverage on the BBC and went to bed on election night with Gore’s victory in Florida confirmed, as well as his victory in the election as a whole. But in the morning, one of my housemates urgently awakened me with a worried tone of voice. He said something like, “Come look at the TV, something weird is happening.” I stumbled out of bed and made my way to our television set. On it, I saw two BBC newsmen gravely shaking their heads with depressed concern. They said something about how in a very strange and inexplicable turn of events, Florida was now being called for Bush, and if so, the presidency would go to him. The vote count would be contested.

I felt like I’d fallen asleep in one universe and woke up in an alternate bizarro universe. The election aftermath and debacle unfolded over the next month. The coverage I received from the British press made it very clear to me that the Republicans were stealing the election in Florida, had rigged the butterfly ballots to confuse voters into accidentally voting for Pat Buchanan instead of Gore, and were doing everything they could to prevent a proper recount of the ballots. I had eschewed both candidates, voting Libertarian that year, but I felt astonished, outraged, and broken inside when the Supreme Court stepped in and voted on 5-4 partisan lines to forbid the continued counting of votes, handing the presidency over to Bush by fiat.

Up to that time, I really believed in America and our democratic system of government. Bush v. Gore crushed that belief. I returned to the US three days after the infamous Supreme Court decision, and my sense of living in an alternate universe continued to compound. I looked around at my fellow Americans, and was astounded to find that no one seemed upset. People were saying things like, “Well, the election was basically a tie, and it had to go to someone, so what’s the big deal?” Meanwhile, I was thinking to myself, “Where are the torches? Where are the pitchforks? Don’t people realize the democracy has just been overthrown?”

I felt the return of the eerie dread I mentioned in reference to the Oswald backyard photo. It now shouted at me on overdrive. It can be useful to take note of this kind of feeling: I experience it as a shiver in back of my shoulders and a hollow pit in my heart and gut. Such feelings are not evidence, and they carry no evidential weight. But they may be signals from our subconscious mind, noticing and incorporating information the conscious mind has not yet integrated. These internal signals should certainly not be relied upon on their own; they can easily be misinterpreted. Their relevance is limited to their role in prompting us to investigate further, in search of consistency through evidentiary analysis and corroboration.

I did investigate. It only took me a few weeks to figure out what had happened once I gained adequate exposure to the US corporate press coverage of the election. I realized that Americans had not been receiving the news coverage I was privy to in England. The entire US press corps was colluding to suppress and obfuscate the clear evidence of a stolen election. Instead of news, they bombarded us with photos of a gnomish, bug-eyed man gazing quizzically at the butterfly ballots in various postures of contrived bafflement. This was apparently meant to demonstrate that determining voter intent on the ballots was a near impossible task that ought to be abandoned—and that the whole issue was a silly joke we needn’t concern ourselves with.

As with the Oswald photo, these images carried the controlling narrative. The facts of the case were secondary and unimportant. The American press went out in force, imploring the public to meekly accept the results and turn against Gore for even insisting on full ballot recounts in the first place. It worked.

The stolen election became the impetus that led me to finally take a good hard look at the Kennedy Assassination. If the press had aided and abetted the cover-up of the election theft that shifted power from the rightful president to a pretender in 2000, they might previously have colluded in other ways. A big part of the reason I had never deviated from my support for the lone gunman official story was because I couldn’t believe the news media would fail to expose the conspiracy if it had truly existed.

The respectable corporate press was uniform in their insistence that there was no conspiracy. Oswald had acted alone—no conspiracy, no cover-up. He was a lone nut who killed Kennedy for reasons no one would ever comprehend. And Jack Ruby was another lone nut who killed Oswald, also for reasons no one would ever comprehend. There was no need to comprehend their reasons. Life is simple. Nuts are everywhere, and they apparently get very lucky when they attempt to assassinate heavily guarded targets. The government is basically honest. The media is basically honest. Case closed.

That narrative was good enough for me until I was exposed to direct evidence of US media collusion in the 2000 election. The corporate press acted in concert to downplay and cover-up the election theft—to push people into accepting Bush as president without question. Yet I had seen clear evidence of theft in in the British press. The US corporate press wasn’t free—it was controlled. They were all presenting the same story and completely suppressing the other side of that story, which was mainstream news in England.

What other stories had the corporate press colluded to suppress? And for how long? I decided the Kennedy Assassination would be a good test. If Kennedy was assassinated by a conspiracy in 1963, a free press would have exposed this. But a controlled press might have colluded to cover up such a conspiracy, assisting in the transfer of power from the rightful president to a pretender—just as I saw them do in 2000.

If the evidence showed Oswald had indeed killed Kennedy alone, I wouldn’t learn anything about how long ago the press became controlled, but at least I would learn the truth behind Kennedy’s death to my own satisfaction. I had now released the narrative frontloading process that closed my mind to an honest examination of the evidence in the case. I had replaced it with the antidote to narrative frontloading—a process I call narrative frame comparison. In this process, competing narratives are both held as open possibilities and evidence is considered in accordance with both narratives. As more evidence is examined and incorporated, the competing narratives are winnowed down to sharper levels of specificity through a process of eliminating impossibilities.

As the process continues, new narrative frames are suggested by the mounting evidence in question. These are likewise held open in a continuing narrative frame comparison process, and the narrowing of possibilities continues. Over time, some narratives collapse completely under the weight of mounting contradictions, and surviving narratives more closely approach the truth. Along the way, certain evidentiary facts are corroborated to the point that certainty can be reached in a number of areas. By this process, one can develop narratives and worldviews that match the evidence in our world—rather than develop a false or skewed view of the world by distorting and ignoring evidence in service of a pre-selected narrative.

Each of us will encounter many doorways to perception in our lives. If we wish to open these doorways and see the world closer to its true form, we must identify the prematurely adopted narratives that keep those doors locked. When it comes to the Kennedy assassination, the narratives that lock the doorways tend to sound something like this: “The establishment (government, news media, academia, etc.) are not capable of colluding together to cover this up. If they were capable, they wouldn’t do it anyway. There are too many good, honest people who would never go along with the lie. The truth would necessarily win out in at least one of these institutions, and then it would spread to the others.” This narrative frame is often bolstered with bitter laughter and derisive comments about conspiracy theorists, tinfoil hats, mustache-twirling villains, smoke-filled rooms, and the Illuminati.

That kind of narrative frame locks the doors of perception. It used to be my narrative. I used to be the one who laughed bitterly while deriding conspiracy theorists, tinfoil hats, and all the rest. For me, it took the Bush v. Gore election theft to shatter my frontloaded narrative and unlock the doors. For others, it might be something else. Maybe it’s 911, Covid, weapons of mass destruction in Iraq—or maybe the Kennedy assassination itself. Or maybe it hasn’t happened yet.

The only necessary step to unlocking those doors is to hold open the possibility of establishment collusion in propagating falsehoods. Then, using a narrative frame comparison process, compare the evidence in context with the two frameworks: one in which establishment collusion is impossible and never occurs, and the other in which establishment collusion is possible and sometimes does occur.

I suggest the Kennedy assassination as the best place to start. That’s where I started, and that’s why I’m writing these articles. I will provide a guide through the narrative frame comparison process in this case, and explain my reasoning along the way. I believe this processes shows that establishment collusion does indeed occur, did occur, and is still occurring in the case of John F. Kennedy’s murder. This collusion can be identified as serving to conceal the reasons for Kennedy’s murder, the beneficiaries of his murder, and the changed form of American government his murder brought into power. Uncovering the reality of the controlled and coordinated news media is one of the important lessons the Kennedy Assassination teaches us. After recognizing it once, it becomes possible to recognize it anywhere, over and over again.

Diving into the Case

Following the installation of Bush as president and the shock of what had happened with the election, the Supreme Court, and the corporate news media, I became very depressed. It took me until the summer of 2001 to regain the strength and spirit I needed to dive into the Kennedy assassination research. It was the first time I ever made important use of the internet, which I was able to access at the University of Idaho computer labs. A new search engine called Google was rising to prominence (it still provided great results in those days), and I began finding online articles on all sides of the conspiracy debate. I recall stumbling across a website by the name of “mcadams” and found it had a wealth of fascinating information about the case. It took me a few weeks before I realized the information on this website was slanted toward the lone gunman view. By that time I was starting to believe the lone gunman view might have been the correct one all along.

I searched harder for the conspiracy views to see if they could tear down the case made by mcadams and the other lone gunman proponents. These views were more difficult to find than the lone gunman views, but once I did (and after I separated the wheat from the chaff), I began to find that most of the conspiracy views had answers to the narratives and evidentiary interpretations synthesized on the mcadams site. Among the conspiracy views, I also discovered evidence entirely absent from the mcadams site and its presentation of the case.

I became frustrated with the mcadams site and other lone gunman sources; they tended to simply ignore most credible challenges to the lone gunman narrative. Their rebuttals were targeted at the weakest and least relevant conspiracy evidence, and they addressed the stronger conspiracy evidence piecemeal and out of context. The conspiracy views, on the other hand, were well acquainted with the lone gunman perspective and tended to have convincing rebuttals to each and every lone gunman argument, including their best arguments.

The conspiracy viewpoint was starting to win out and become more convincing the more I sifted through the evidence, arguments, interpretations, and rebuttals. I searched for more lone gunman sources, seeking rebuttals I hadn’t found before, but didn’t find much. There was plenty of speculation and conjecture on the conspiracy side, but I began to hone in on a few points that were really solid, backed up by strong evidence, widely agreed upon. Number one on the list was the absurdity of the single-bullet theory. The evidentiary constraints of the lone gunman narrative forces its supporters to believe that a single bullet tore through the bodies of both President Kennedy and Governor Connally (sitting in front of Kennedy in the limo), inflicting seven separate wounds between them via impossible trajectories, and causing no more damage to the bullet than if it had been fired into a tank of water.

I also read about the implausibility of Oswald getting to the sixth floor, assembling the rifle, pulling off two miracle shots and one miss, hiding the rifle, and running down several flights of stairs—all in impossibly tight time windows with no one seeing or hearing him do any of it. He was reported as appearing cool, calm, collected, and unhurried when he was encountered less than two minutes after the shooting. I read about the plethora of contradictions in the case against Oswald as the murderer of police officer JD Tippit less than an hour after Kennedy’s assassination. I found the circumstances of his arrest highly suspicious, with dozens of police swarming in on him at a movie theater about 30 minutes after the Tippit shooting, supposedly because he did not buy a ticket. There seemed to be no reason or indication for them to suspect Oswald in the shooting of Tippit until they had already arrested him for it.

The weeks went by, and the evidence kept mounting in favor of Oswald’s innocence and multiple shooters in the Kennedy assassination—but I wasn’t convinced yet. There simply had to be good counter-arguments to the conspiracy evidence. Yet again and again, I found that the lone gunman arguments misconstrued and straw-manned the conspiracy evidence. They cherry-picked facts and ignored challenges they couldn’t answer. They took their critics’ arguments out of context and resorted to ad hominem attacks, appeals to authority, and appeals to narrative—and then would go back to repeating their own evidence over and over, even when their evidence had already been challenged with critiques they couldn’t answer.

I was still investigating, still uncommitted in belief, but I was nearing the threshold of shifting my opinion to favor the conspiracy view. Then 911 happened, sending me into sudden shock. Within hours I observed the corporate press rush forward in unison to announce that Osama bin Laden and his 19 hijackers were the culprits. Every outlet had the same story—no outliers. They immediately started to talk about how “of course” the US would have to invade Afghanistan. These were presented as foregone conclusions—just like with the Kennedy assassination. The targeting of Oswald as the lone assassin appeared to be a pre-arranged, pre-packaged story, launched within hours of Kennedy’s death… just like the story about 911.

I began to smell a rat, and I was getting that familiar eerie feeling of dread about 911 and how the government and media were responding to it. I wasn’t sure what was true and what was a lie, but I immediately felt suspicious of official deception underway somewhere in this event. I even heard the press talk about how we could all agree what a relief it was that Bush had become president and Gore had lost—what terrible shape we’d all be in if we were stuck with Gore as president at this moment. This narrative, parroted on numerous media outlets, tied the event back to the stolen election.

A few days after 911, I returned to the computer lab to renew my research in the Kennedy assassination, and a strange thing occurred. I was struck with a feeling of guilt, accompanied by the thought that it was irresponsible for me to explore the possibility of governmental complicity in Kennedy’s death and the ensuing cover-up. After all, in light of what had happened on 911, shouldn’t we all be pulling together? Didn’t my country need my support instead of my suspicion? Maybe I owed it to my country to set this investigation aside and demonstrate some patriotism.

The thought stayed with me only a few minutes before I became shocked and disturbed I had even entertained it. The experience showed me how powerful authoritative pressure could be. My research into the Kennedy assassination was not motivated by a desire to falsely smear the government. It was motivated by a desire to know the truth. I would be quite satisfied if my research led me to conclude that agents of the government were not involved in Kennedy’s death in any way. In fact, if the evidence led me to that conclusion, I would feel greatly relieved.

But if the government was involved, the people needed to know. If that knowledge led to suspicions about the government’s involvement in 911, so be it. The government had nothing to fear from honest scrutiny—unless it was compromised. I would actually be derelict in my duty as a citizen and patriot if I stopped pursuing the truth about the Kennedy assassination out of fear of what I might find. And if I found government was blameless in the assassination, I would be in a great position to spread the news that we could trust our government after all, and I could back this up with evidence and reasoning. My service to the country and the world would be to continue following the truth wherever it led me.

So I decided to carry on. I realized I needed to view the Zapruder Film and see for myself if I could glean anything from it. This was an 8mm film of the assassination recorded by Abraham Zapruder on his own home camera at the time Kennedy was shot in Dealey Plaza. There was no YouTube in 2001, nor online video of any kind, so I had not yet witnessed the film through my internet research.

I happened to work at an excellent local video rental store at the time, and I discovered we had a copy of the Zapruder Film in stock. We also had a documentary on the assassination, entitled The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes. I took both videos home with me, along with a copy of Oliver Stone’s JFK, which I still had not yet seen.

I was shocked when I watched the Zapruder Film. This is the third doorway into the case. If you’ve never watched it, don’t waste any more time and watch it right away. The film is gruesome and it hurts the heart to witness the destruction of John F. Kennedy’s head, mind, and life. But it is important as evidence because it clearly shows that when Kennedy was struck by the fatal head shot—his head, shoulders, and entire upper body were thrown violently backwards and to the left. And the reason this is important is because the official lone gunman narrative of the case requires that all of the shots were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald from the Texas School Book Depository, a building that was located above and behind Kennedy.

Kennedy was slumped forward with his head angled down before the fatal shot was fired—bent in agony due to the shot (or shots) he had already been struck by. There is only one reasonable way to explain how the impact of the shot lifted his head, flipping it backward and to the left, while also markedly shoving his shoulders and entire upper body backward and to the left. The shot that killed Kennedy could only have been fired from in front of him, striking the right side of his head. It could not have been fired from the Texas School Book Depository—not by Oswald or anyone else located in that building. View the Zapruder Film for yourself by clicking on the image below:

Upon witnessing it for the first time, that eerie feeling came back to me once more—that same hollow pit in my heart and gut, that same tremor in my shoulders. I couldn’t understand how anyone could view this film without immediately concluding that Kennedy was killed by a shot from the front. The suggestion that this shot could have come from behind is quite frankly absurd. An overwhelmingly deliberate, rigorous, and conclusive explanation would be required to believe otherwise.

Oswald was supposed to have shot Kennedy from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository. With a shot angled down on Kennedy from above and behind, and with Kennedy already slumped forward, the president should have been pitched downward and forward if that story was true. The US Government and the corporate press had been deliberately ignoring and dismissing this obvious evidence for decades. They had been gaslighting the American people all these years.

Actually it was worse than that. I next watched The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes, the documentary by John Barbour. This documentary is currently free to watch on YouTube, and I recommend it as a presenting a good cross-section overview of the case. In that documentary, I was introduced to a clip of Dan Rather from three days after the assassination. He had just watched the Zapruder Film, representing CBS in a bidding war with Life Magazine for exclusive ownership rights. (Life Magazine won out in the bidding, and the Zapruder Film would lay sequestered in its vaults, hidden from public view for years to come.)

Watch the clip here to see Dan Rather recounting what he claims to have witnessed on the Zapruder Film in a news broadcast. At minute 2:07, you can watch him blatantly lie to the American people, telling them the film showed that Kennedy’s head was moved “violently forward” by the fatal head shot. By this time, Oswald had already been assassinated by Jack Ruby. And future CBS national news anchor Dan Rather was already colluding to spread the official lie that Oswald killed Kennedy, acting alone.

Life Magazine prevented the American people from viewing the Zapruder Film for the next 12 years. Only bootlegged copies were available, circulating in the underground until assassination researcher Robert Groden secretly obtained a copy of the original, stabilized it, and eventually arranged to air it on network television in 1975. Both the FBI and the Warren Commission (the blue ribbon panel hand-picked by Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, to investigate Kennedy’s assassination) had ignored and misrepresented the evidence shown in the Zapruder Film, as did Life Magazine when they published still frames from the film in misleading context.

The American public was unable to discover these misrepresentations until 1975 when the film was finally shown on television. For the first time, viewers saw the clear evidence of Kennedy’s death by a frontal shot with their own eyes. The outcry that followed led the US Congress to form the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) which reinvestigated the case in the late ‘70s. Although the committee concluded that Kennedy was killed by a conspiracy with more than 95% certainty, they simply referred their findings to the US Department of Justice, which took no action.

On its face, the Zapruder Film presents powerful evidence that Kennedy was killed by a frontal shot. This evidence was misrepresented and suppressed by US official investigating bodies and the corporate press—colluding to perpetuate a cover-up—deceiving the public about how their president was killed and removed from power.

When I finally watched Oliver Stone’s JFK, I found the film presented the basic research in the case fairly well, in addition to telling the story of Jim Garrison, the New Orleans District Attorney who investigated the JFK case in the late ‘60s. The film pairs nicely with the previously mentioned documentary by John Barbour, which lays out the evidence in the case in more detail than was possible in JFK, and tracks the story of Garrison’s investigation to provide additional context to what is presented in Oliver Stone’s film.

The Zapruder film, supplemented by the two films mentioned above and the research I had already conducted, completed my journey through the Kennedy assassination doorways. The lone gunman narrative had collapsed under the weight of the evidence. So did the narrative I used to believe about how the establishment couldn’t have colluded together to deceive the public about something like this.

I now believed that Kennedy had been killed in a conspiracy involving multiple shooters, that Oswald was not one of those shooters, and that Jack Ruby had been a member of this conspiracy and assassinated Oswald to silence him and protect the other conspirators from exposure. I was also convinced that the US Government and corporate press had colluded in a cover-up to distort and suppress the true facts of the case, frame Oswald as the lone shooter, and impose a false narrative on the American Public about what had happened to their president and their country.

This cover-up and deception began in 1963, was still in place in 2001, and continues to this day in 2024—61 years after Kennedy’s murder. I believed the likely motive behind Kennedy’s assassination was to facilitate America’s full-scale entry into the Vietnam War, to perpetuate the Cold War as a whole, and to enable continued expansion of the global US Empire system. Kennedy was an obstacle to those goals. His murder and the ensuing cover-up paved the way for perpetual rule by the military-industrial state and the network of financiers who control it.

These understandings came to me at a time when I was watching the United States lose its collective mind in the wake of 911—pounding the drums of war and showering George W Bush with a 90% approval rating as he instituted a permanent warfare and surveillance state. His enormous public support baffled me, having come in response to Bush presiding over the worst national security failure in the country’s history (and 10 months after stealing the election to assume power in the first place). I trusted nothing about the 911 narrative. I continued to observe many parallels between the unfolding of that narrative and the unfolding of the Lone Nut Oswald narrative in the Kennedy case—right down to the slavish complicity of the corporate news media in bolstering the false realities promoted by the US Government to service its military ambitions.

The Gaslighting Effects of Propriety

In the years following 911, through the launching of wars on Terror, Afghanistan, and Iraq—dissent was taboo. Thanks to the Kennedy assassination, I saw through the deception of these events almost immediately (in the case of 911) and before they happened (in the case of each successive war). I was in lonely company though, and I dared not speak of such things to most others. In the jingoistic mood of the time, my views were considered traitorous to many.

A friend who shared my perspective advised that I ought to lie to people and tell them I believed in the official narratives of both 911 and the Kennedy Assassination. He argued that people were simply not willing to listen to anyone who rejected these official narratives. Once they learned what my views were, they would fear me and lose respect for me. It was better, he argued, to outwardly accept the official lies so others would still listen to what I had to say. Then I could try to persuade them to reject the US policy of infinite warfare from within the false narratives.

The same friend also suggested an interesting take on the intelligence agencies, military leaders, and secret societies full of oligarchs I became aware of through my Kennedy Assassination research. His suggestion was uncanny in its resemblance to a central tenet later embraced by the QAnon movement and adherents to the cult of Trump: that undercover “white hats” might be hard at work in the hallways of secret power to expose and overthrow the conspiratorial “black hats.”

These white hats would publicly proclaim their loyalty to the official cover story narratives, enabling them to work for good behind the scenes. Back in 2002, my friend didn’t use the term “white hats,” but his advice was essentially that we should both join the ranks of those who publicly endorsed the prevailing false narratives so we could maximize our ability to do good as enfranchised members of mainstream society.

I disagreed with my friend’s approach as soon as he suggested it. I refused to lie about my beliefs and understandings regarding what was true. But I saw how his perspective could be convincing to others who sought to play the game and gain a seat at the tables of power. It gave me hope that maybe there were people working within the system to change it for the better once that was finally possible.

These vain hopes would be ruthlessly crushed in the years to come, but that’s another story. In the meantime, I realized it was largely useless to tell most people what I believed about topics generally dismissed as “conspiracy theories.” I wouldn’t go along with the lies, but I mostly kept my mouth shut. I only disclosed my views to the few people who displayed openness to considering my perspectives and the reasons behind them.

Coerced silence in the face of overwhelming social majorities has a gaslighting effect on the mind. Self-doubt creeps back in. Did I make a mistake in my analysis of JFK’s assassination? So many people were so sure of themselves. Maybe Oswald really was the shooter. Those backyard photos really were authentic. Oswald’s impossible lean was a trick of the eye. Maybe that magic bullet he fired really could have done everything people said it could. Somehow the head shot from behind Kennedy really could throw the president backwards on impact. Jack Ruby really was just a concerned citizen motivated to kill Oswald in a sudden impulse of vigilante justice.

After all, this lone gunman position was the one adopted by luminaries like Noam Chomsky. Many of us opposing the War on Terror looked to Chomsky as a lifeline in those days. His claim to fame lay in his incisive deconstruction of corporate media and government propaganda. If Kennedy really was killed in a conspiracy, how could a brilliant mind like his—trained to dismantle official deception—be misled in the Kennedy case? How could I possibly claim to be smarter than Chomsky on this?

Chomsky insisted that even if a conspiracy had killed Kennedy, it wouldn’t matter. Kennedy was a Cold Warrior, a true blue anti-communist crusader and warmonger—the man truly responsible for Vietnam. If a conspiracy had killed him, the reasons behind it would be inconsequential, as would the impact on US policy. Perhaps I had been wrong about Kennedy. I had been listening to unserious people like Jim Garrison and Oliver Stone instead of the legitimate leaders of the Left like Chomsky. Perhaps my responsible duty was to ditch all this conspiracy theory drivel and line up behind Chomsky and other left-wing leaders to fight the capitalist war machine.

After years of wrestling with the gaslighting I received from both the corporate establishment and thinkers like Chomsky, I now see that Chomsky had taken precisely the approach my friend had suggested. He wasn’t going to discredit and marginalize himself by challenging the official narratives on 911 or the Kennedy Assassination. He was going to go along with the lie and use the credibility maintained by doing so to promote his goals for political change. To facilitate this, he was engaging in his own version of narrative frontloading—selecting a narrative about Kennedy and his assassination before the fact, and insisting that whatever the evidence shows, it must necessarily confirm his selected narrative.

It is easy to identify the secondary gains that narrative provided him. Secondary gains are personal benefits made available through adherence to a frontloaded narrative, or by the alteration or fabrication of evidence (by witnesses, law enforcement, or interested third parties). These benefits may include wealth, access to opportunity, social propriety, or even preservation of life and limb. Other varieties of secondary gains include psychological benefits such as notoriety, feelings of peace or security in one’s worldview, or the bolstering of a favored ideology.

Chomsky’s adherence to the official narrative ensured he would not be marginalized. Instead, his voice could be amplified, furthering his career goals and public profile. It would aid in the proliferation of his anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist political message, which in Chomsky’s view would improve the world. In contrast, conceding that a liberal capitalist politician like Kennedy could also have anti-imperialist views and policies (and that he was killed in a coup because of this) would undermine and contradict Chomsky’s entire political position. Chomsky insisted that liberalism was inextricable from imperialism and only a socialist (or otherwise leftist) political approach could lead to moral outcomes. The official narrative accepted by Chomsky in the Kennedy assassination must be the true narrative, because accepting it led to outcomes and implications Chomsky believed were right and true (while incidentally benefitting Chomsky himself).

I cannot actually know Chomsky’s true motivations in dismissing the facts of the Kennedy assassination (along with the facts pertaining to other deep political events like 911 and Covid). In recognition of this, I’ve presented the secondary gains available to him in terms of their tangible benefits. This stricture is necessary in order to refrain from psychological gain projection when considering an opposing narrative or when evaluating witness credibility.

Psychological gain projection is a tool in service of narrative frontloading in which speculative psychological benefits are projected onto another person in an attempt to discredit their evidence, testimony, or reasoning. Common examples in the Kennedy case include statements by lone nut proponents such as, “Conspiracy theorists are motivated to invent elaborate plots in order to direct their frustration at an imagined powerful enemy in the shadows,” or, “Conspiracy theorists just can’t handle the fact that an obscure person like Oswald was able to kill the president and change history.”

One could just as easily contend that lone nut proponents are motivated to ignore evidence of conspiracy because the idea of a powerful enemy in the shadows depresses or frightens them, or that they are motivated by feelings of comfort and inspiration in the idea that obscure people can single-handedly change history. This kind of retreat into narrative frontloading gets us nowhere and should be avoided altogether. In the case of Chomsky, I used his example to introduce the concept of secondary gains, the role of secondary gains in establishing frontloaded narratives, and to demonstrate the utility of recognizing tangible secondary gains (concrete gains that can be used to evaluate credibility) in considering the reliability of witnesses and sources.

The reasoning Chomsky has given for his acceptance of the official narrative reveals that he is engaging in narrative frontloading with the Kennedy case. So does his choice to ignore examination of facts in the case. Chomsky’s analysis of Kennedy as warmonger serves his frontloaded narrative, but it ignores JFK’s promotion of peace through détente and backchannel negotiations with the Soviet Union; his passage of the first nuclear test ban treaty; his persistent efforts to avoid going to war in Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam; and his support for neutrally-aligned third world nationalism in Algeria, the Congo, Indonesia, Egypt, and elsewhere.

Psychological gain projection is even more important to avoid when analyzing the evidence in the case than it is in analyzing the perspectives of high-profile commentators like Chomsky. For instance, if I believe the evidence shows Lee Harvey Oswald killed Kennedy, the tangible secondary gains available to Oswald through that act should be identified to check for consistency. If no such gains can be identified, the theory of Oswald’s guilt is weakened but not disproven. If such gains are identifiable, the theory of his guilt is strengthened but not proven.

In this case, psychological gain projection would consist in reasoning from a speculative claim about Oswald’s motives: e.g., Oswald was a misfit who longed to be special. Killing Kennedy would satisfy this need for specialness, establishing secondary gains for Oswald in achieving the assassination. Now that I have used psychological gain projection to establish a frontloaded narrative prior to examining the evidence, I can used this established bias to scan the case for evidence that supports my frontloaded narrative and discount evidence that does not align with it.

Returning again to the question of commentators or researchers in the case, psychological gain projection in the case of Chomsky would consist of dismissing his theory of the case before hearing him out—because I’ve projected a narrative onto him that discredits his perspective. A tangible secondary gains analysis, on the other hand, seeks to understand why Chomsky would endorse the official narrative of the assassination after already noting that Chomsky’s take on the case and the evidence is superficial, it is out of alignment with his reputation as a fierce media critic, and it employs a distorted analysis of President Kennedy’s foreign policy, ignoring his support for Third World self-determinism, deescalation of the Cold War, anti-imperialism, and peace generally—all of which are policy objectives Chomsky purports to have favored.

The truth about Kennedy’s foreign policy is crucial to understanding why his assassination benefited the imperialist aims of the military and financial interests who opposed him. I have offered my analysis of the tangible secondary gains available to Chomsky (protection from marginalization, career advancement, promotion of an invested ideology) as a case study in how secondary gains can be influential factors that encourage narrative frontloading.

In my first article in this series, What the JFK Assassination Can Teach Us, I make reference to the concept of experiments in truth. In my experience, truth is usually not the highest priority in human belief or behavior. Secondary gains are usually prioritized over truth. Truth is often regarded as so malleable, we may even lie to ourselves about our prioritization of secondary gains over truth—and convince ourselves we are not lying.

As such, prioritizing truth above secondary gains is indeed an experiment. It asks us to seek truth and emphasize truth—not because it promises to benefit us—but as an act of spiritual devotion and faith. We can’t be certain how (or if) the truth will benefit us or the world, but we take a chance on it anyway. Something about truth calls to us. In an experiment with truth, we observe with curiosity to discover the outcomes rendered by the path of truth.

Clarity of Mind Through Narrative Frame Comparison in the Kennedy Case

In the years following those dark and frightening days in the early 2000s, when Noam Chomsky still seemed like a hero, my confidence in the truth of the conspiracy behind JFK’s death ebbed and flowed. But even at its lowest ebb, I never leaned back into believing JFK was killed by Oswald, the lone gunman. The evidence for multiple shooters and the framing of Oswald is simply too strong. So is the evidence that Kennedy was seeking peace, and that figures tied to the assassination were motivated by desire for continued war (along with opposition to other Kennedy policies).

Twenty years ago, good evidence in the case was still hard to separate from the bad. I held many of uncertainties about what had really happened and how to make sense of the details in the case. But in the years since, dedicated researchers have done stellar work to identify and sequester poor evidence and false leads in the case, and expand upon the evidence that stands up to scrutiny. This work has been bolstered by the steady integration of documents declassified through the JFK Records Act.

In my recent article, Swimming in the Ocean of Lies, I describe the challenges of belief at this moment in history, compounded by ongoing advances in AI technology and its ability to fabricate images and voices. It is a time of narrative warfare. Every major institution has compromised its authority and trustworthiness through repeated deception. Members of the public increasingly export their own discernment of reality to idolized leaders in desperation. Others reach for ideological purity to filter reality for them. Others vacate the field of reality-testing and belief-formation entirely. Others still drift into Gnostic nightmares of a totally simulated reality, assuming that every aspect of our reality is a controlled manipulation.

Bombarded by narrative warfare in every direction, the sovereign mind requires tools of contextual narrative reasoning to navigate through the Ocean of Lies and resist falling prey to false beliefs that serve the agendas of aspiring power-seekers. The Kennedy assassination is an excellent domain in which these narrative reasoning tools can be learned, tested, and applied.

Thanks to the excellent Kennedy assassination research that’s been done this century, we can untangle webs of deception and gaslighting and recognize that it really is possible to build our beliefs on solid ground. Absurd conjecture, deliberate disinformation, false leads, hucksterism, and limited disinfo hangouts can be sorted through and dismissed. The elimination of impossibilities sharpens the scope of what can be known. The mind is trained and strengthened through the process. In 2024, I gained solid confidence in my understanding of the Kennedy assassination, and my ability to navigate through today’s narrative wars was strengthened in the process.

The three doorways of entry to the Kennedy case I presented in this article dismantle the presumed truth of the official narrative. The doorways do not establish dispositive truth in the case—they insist that any narrative, official or otherwise, provide an accounting for these doorways and what they show. Through the story of my own entry into the case, I demonstrated how frontloaded narratives are able to keep the doors of perception locked. We’re often unaware of the narratives that blind our vision. These narratives sometimes operate in subconscious collusion with the secondary gains available to us by staying blind. Other times it simply hasn’t occurred to us that many of the truths we take as a given are actually prefabricated narratives that limit our perception.

Sometimes the keys that unlock these doors come unbidden, crashing through our frontloaded narratives like a wrecking ball demolishing a paper house. That’s how it happened for me. But if we prefer a gentler and intentional method of enlarging our scope of vision and feel called to engage in experiments with truth, the keys can often be found through the process of narrative frame comparison.

By paying attention to questions that tug at the edge of our mind—sometimes accompanied by an eerie feeling that something doesn’t feel quite right—doorways to perception can come into focus. From there, competing narratives that flow from any question of fact can both be held as open possibilities. Evidence and reasoning can be considered in accordance with both narratives, guiding us through the doorways and closer to truth.

In Part Two of this article, I will take a deeper look at each of the three doorways identified here, explore the context that informs them, and apply the method of narrative frame comparison to explore the path beyond each doorway. Along the way, I will continue to introduce and apply narrative reasoning tools that can assist in navigating the frame comparison process. I’ll also identify additional pitfalls and narrative fallacies that can lead the mind astray and bewilder our perception.

After encountering the doorways to perception and discovering the keys that unlock them, the next step is to see where those doorways lead and what the world looks like on the other side.

Relendra’s series of Kennedy Assassination Articles

While it is outside the scope of this series of articles to provide footnotes or citations for much of the evidence presented here, I have compiled a resource guide to encourage readers to verify the facts of the case for themselves: a compendium of the books, websites, podcasts, films, and methods of research available in researching or learning about the Kennedy case, complete with links.

An intro to the discipline and benefits of understanding the assassination of John F. Kennedy—with reference to its utility and applicability in understanding power dynamics and narrative reasoning on the macro scale of history and global politics, now and then, as well as in one’s personal relationships and spiritual journey.

An introduction to three images that open the mind to the Kennedy Assassination—and a guide to the process of encountering the doors of perception and the keys that unlock them.

A deeper exploration of the path beyond the initial doorways of the Kennedy case through narrative frame comparison, guidance in the use of narrative reasoning tools, and identification of reasoning pitfalls and narrative fallacies. The backyard photos and the circumstances surrounding them are held to particular scrutiny. The case for seriously questioning the official narrative of the assassination is firmly established.

An exploration of the medical and ballistic evidence in the Kennedy Assassination, using narrative frame comparison to eliminate impossibilities in two competing narrative frames: Kennedy was assassinated by a single gunman, or Kennedy was assassinated by multiple gunmen.

In continuing the process of eliminating impossibilities through narrative frame comparison, the evidence against Lee Harvey Oswald is examined in detail. Through this examination, the exoneration of Oswald is established. Oswald did not fire any shots at Kennedy, nor did he participate in the assassination. Multiple gunmen fired at Kennedy, but Oswald was not one of them.

Two men, Ralph Yates and Buell Frazier, both testified to transporting Lee Harvey Oswald to the Texas School Book Depository—and that Oswald bore a package with him he described as containing curtain rods. In examining the reports of both men through narrative frame comparison, it can be established that Yates did transport a hitchhiker claiming to carry curtain rods, but it wasn’t Oswald; and Frazier did transport Oswald, but Oswald didn’t carry a curtain rods package. The intersection of these stories provides strong evidence that Oswald was framed for Kennedy’s Assassination prior to its occurrence and that members Dallas Police Department assisted in framing Oswald, possessing foreknowledge of the plot.

A glossary of terms to aid in the process of contextual narrative reasoning. Includes descriptions of narrative fallacies and narrative reasoning tools, with examples and application to the Kennedy assassination case

To this author and any others who take an interest: Two essential books that remove any doubt about government conspiracy to kill JFK and Oswald's innocence:

JFK and the Unspeakable by James Douglass and

Me and Lee by Judyth Vary Baker about the intimate relationship with the man in the summer of 1963. Both have abundant documentation.